Every holiday has its centerpiece, its symbol, and none is more rich and varied than the Passover Seder plate. Each item has been the subject of generations of scholarship and debate, while the diversity of traditions on display speaks eloquently to three thousand years of Jewish history in countries and cultures all over the world. Who knew that eggs and horseradish could be so interesting?

Haggadah

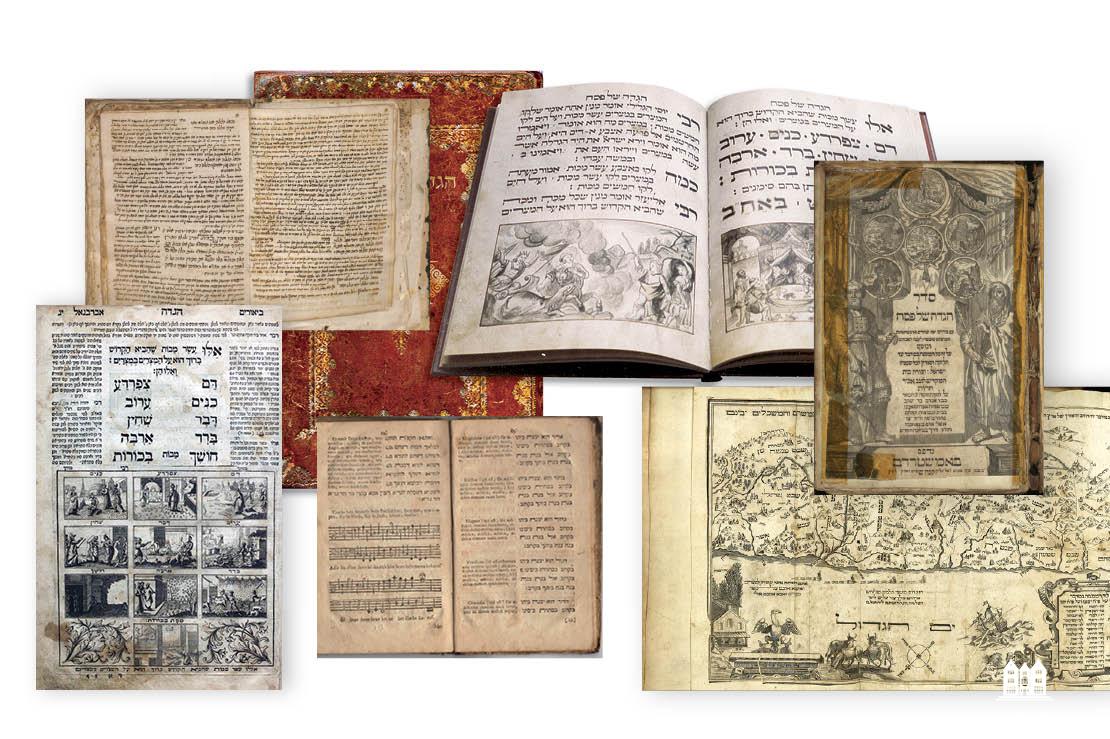

Since escaping Egypt, the Jewish people have celebrated Passover by telling the story of the Exodus. Over time, the story became more formal and elaborate—the word seder means “order”—as customs developed and coalesced. Around the turn of the previous millennium, a selection of scriptural verses, a Mishnaic-era exegesis, and a guide to the laws and customs of the Seder night were compiled into a single text, and the Haggadah was born. The oldest physical fragments of a Haggadah (literally “to tell”), found in the Cairo Genizah, date back to roughly this time. Since then, the text has gone on to inspire an astonishing array of versions, commentaries, and companion works—more than any other book in the Jewish library excluding the Bible. According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica, since the fifteenth century there have been more than 2,700 editions!

Matzah

On all other nights we eat leavened and unleavened bread—tonight, only Matzah. The puffed-up and inflated character of bread, the Chassidic masters tell us, represents arrogance and ego, the inclination to evil itself. “Master of the Universe,” the Talmudic sage Rabbi Alexandri used to pray, “our will is to perform Your will, yet what prevents us? The yeast in the dough . . .” (Talmud Bavli, 17a). Strange, then, that we are so committed to eradicating chameitz on Pesach, but tolerate it the rest of the year.

The ego is an unavoidable part of the human condition, but it doesn’t need to be its organizing principle. For eight days, we surrender to a higher consciousness, an exercise in extremes meant to reorient our lives toward a higher purpose. Not just the base of the Seder plate, the matzah is the basis of the entire year.

Wine

The Kiddush cup is only the first of four drunk at the Seder. According to the Jerusalem Talmud, these cups of wine correspond to four promises G-d made to the Jewish people: “I will take you out . . . I will save you . . . I will redeem you . . .” and finally, “I will take you to Me as a people.”

The Israelites were rushed out of Egypt in a daze. Degraded by years of oppression, it would take time for them to process the remarkable relationship G-d had just initiated with them. All four “expressions of redemption” reflect this dynamic: G-d is the active agent, while we are passively acted upon. The last one, however, puts the ball in our court: Whether we are truly worthy of being called a “G-dly people” depends on us.

Zroa

The roasted chicken shankbone, or neck bone, in Chabad custom, represents the paschal offering.

In Temple times, each paschal lamb was brought by, and then subsequently distributed among, a mini-collective, like a large family or a few neighbors. While all other sacrifices are either individual or communal, the paschal offering was somewhere in between, or both at once.

Passover reminds us that we have both individual and communal identities. At times, these identities can clash, and we are called upon to rise above our narrow personal preferences on behalf of a greater whole. But the inverse is also true: no community is ever too big or important to let the needs of an individual member go unnoticed.

Beitzah

Like the roasted zroa, the cooked egg (roasted or boiled) on the Seder plate symbolizes one of the sacrifices brought in the Temple: the Chagigah, a “festive” offering that ensured there would be plenty to eat on the holiday. In many communities, the egg is peeled and eaten around halfway through the Seder, just before the main meal.

The egg is a symbol of latent birth. It is both fully formed, and not quite there, the birth only complete after the hatching. The Rebbes of Izhbitz explain that Pesach signifies only the beginning of a process that was fully realized with the giving of the Torah on the holiday of Shavuot. Even now, we recognize that the Exodus story remains incomplete until the future, ultimate redemption.

Charoset

From Morocco to Russia to the Italian Piedmont, there have been more takes on charoset than on any other Seder-plate fixture. Chabad’s minimalist version blends apple or pear together with walnuts and wine, although some texts recommend adding cinnamon and ginger, and the Arizal, that great mystic of Safed, was said to use seven kinds of fruit and three spices.

The name of the dish comes from the Hebrew for clay, cheres, since its paste-like texture is meant to recall the mud and mortar that the enslaved Israelites worked with in Egypt. Maimonides makes this clear with the recipe included in his twelfth-century magnum opus, Mishneh Torah: “How is it made? Take dates, dried figs, or raisins and the like, crush them, add vinegar, and mix them in with spices, just as clay is mixed into straw.”

Maror

Bitter herbs, intended to recall the sharp sting of slavery, are eaten twice during the Seder: First alone and then inside Hillel’s famous matzah sandwich. Both times, however, the discomfort caused by the maror is tempered by lightly dipping the horseradish or romaine lettuce into the sweet charoset relish.

One might wonder: If tonight is all about celebrating the sweet taste of freedom, why are we eating maror at all? In truth, says Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh Leib Alter of Ger, the bitter and the sweet often come together. In Egypt, the depths of our suffering prompted G-d’s miraculous intervention, and as we look back, we see how the slavery itself was just a step on the long road to true national liberation—this was G-d’s plan all along. So too, at the Seder, we wrap the bitterness of exile together with the bread of freedom. Suffering has a way of clarifying things, of ultimately leaving us stronger and more determined.

Chazeret

The Mishnah lists five different vegetables that may be used to fulfill the obligation of eating bitter herbs at the Seder. There is some disagreement regarding their modern-day counterparts, but tradition holds that one, called tamcha, is horseradish; and another, olashin, endives. The most common is chazeret, romaine lettuce.

According to the Talmud, chazeret is the preferred bitter herb, because, when left unharvested, the sweet leaves of the lettuce turn bitter and unpleasant, much like the Israelites’ experience in Egypt. In colder climates, however, such lettuce can be hard to come by in the spring. So for many Jews in Northern and Eastern Europe, horseradish became the herb of choice, and the custom stuck. In Chabad, the lettuce and the horseradish are used together for both the Maror and Korach stages of the Seder, and are therefore placed on both spots of the Seder plate.

Karpas

Several reasons have been suggested for the odd custom of dipping karpas—traditionally onion, potato, or parsley—in saltwater on the Seder night. The classic explanation, however, is just that: it’s odd. It is the first thing we do at the Seder that is conspicuously different from a regular Friday night meal: We make Kiddush, wash our hands, but then, instead of eating bread, we veer left, and dip an onion in salt water. This ploy is specifically intended to catch the attention of the younger Seder-participant, “to intrigue the children,” as it says in the halachic literature.

In our day, efforts to attract the next generation to the Seder continue. There are Passover-themed hand puppets, Martha Stewart-endorsed DIY Ten Plagues kits, and extravagant afikoman prizes. No matter how sophisticated or simple, the object remains the same: to make the Exodus story relevant and engaging to even the littlest among us. It’s the job of every parent and Seder-leader to include everyone at the table—especially those who might one day be leading a Seder of their own.

This article appeared in the Lubavitch International Magazine – Spring 2021 issue. To subscribe and gain access to previous magazines please click here.

Be the first to write a comment.