Teacher, preacher, proto-Chasidic outreacher? How Rabbi Moshe Alshich’s new approach to Torah teaching in sixteenth-century Safed prefigured the Chasidic movement two centuries later and half a world away.

A Synagogue, a City, and a Story

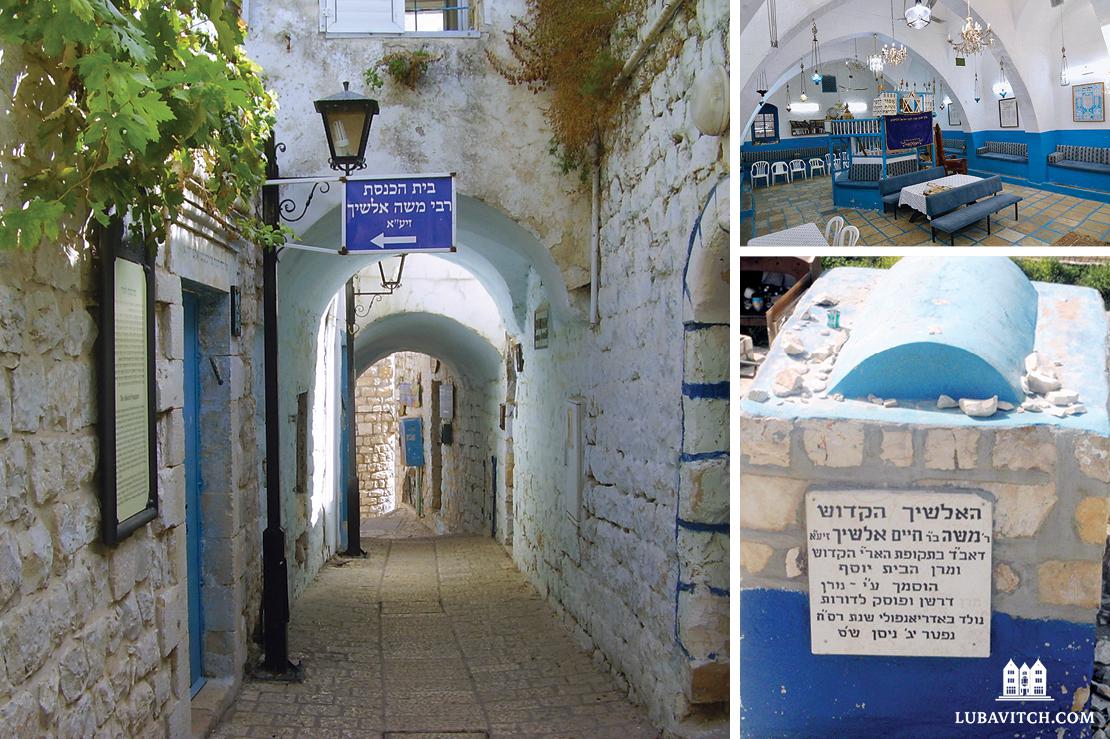

Not far from the art galleries that fill the Old City of Tzfat, or Safed, just off Abuhav Lane, sits one of the city’s many historic synagogues. At the synagogue’s entrance, beneath overhanging vines, reads an inscription engraved into the stone that frames the shul’s blue door: “This is the synagogue of Rabbeinu Moshe Alshich, may his merit protect us, Amen.”

The Alshich’s shul is not quite as well known as the magnificent Abuhav Synagogue just a few doors down, or as busy as the Kossover congregation nearby. Nevertheless, this synagogue, and more precisely the personality behind it, is an indispensable part of Tzfat, which is in turn pivotal to the making of modern Judaism: Over a few exhilarating decades in the sixteenth century, this little holy city on a hill in the Holy Land shone with a light as bright as any other in Jewish history.

It was then and there, in the hills of the Upper Galilee, that Rabbi Yosef Karo produced the Shulchan Aruch, an abbreviated Code of Jewish Law that still sets the pace of Jewish observance and halachic scholarship. A new prayer service emerged with the introduction of Kabbalat Shabbat, anchored by Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz’s paean to the Shabbat bride, Lecha Dodi. The towering presence of the Ari (Rabbi Isaac Luria, also known as the Arizal), along with that of figures like Rabbi Moshe Cordovero and Rabbi Eliyahu de Vidas, brought Tzfat into fame as a city of mystics. It was a moment of extraordinary spiritual creativity and religious dynamism — a magical juncture of place, time, and people.

The Holy Alshich, as he is sometimes called, fit seamlessly into this scene. Rabbi Yosef Karo was the Alshich’s teacher, and he in turn taught Rabbi Chaim Vital, the Ari’s preeminent disciple, in the exoteric law. He was a colleague of Rabbi Alkabetz, and like him composed poetic, Kabbalah-infused prayers, one of which is included in the midnight Tikkun Chatzot rite.

Notwithstanding all of these connections and his accomplishments as a liturgist, a legal scholar, and a Kabbalist, the Alshich is above all — and somewhat by accident — most famous as a sermonizer. As a gifted preacher, he came to popularize some of the esoteric and mystical ideas that filled the air in the Galilee at that magical time. Shimon Shalem, author of a 1966 book on the Alshich, writes that “Alshich filled an important role as a bridge between two worlds, both by constructing a worldview that effaced the differences between them, and by preaching a simple, normal path of divine service that was still in accord with fundamental Kabbalistic beliefs about the world, and about the Torah.”

Ascent to Tzfat

Moshe Alshich is believed to have been born in 1520, but perhaps as early as 1508, in Adrianople, a city in the European side of present-day Turkey. After the catastrophic expulsions from Spain and Portugal just a few years prior, Adrianople had become something of a gathering place for the deluge of Iberian Jewish refugees. It was there that the Alshich would have first encountered the great Rabbi Yosef Karo, before either of them had emigrated to Tzfat. He also studied under Rabbi Yosef Taitazak in Salonika.

Our people have been blessed with many great sages, but very few have the honorific “holy,” attached to their names.

As the Alshich would later write in the introduction to Chavatzelet HaSharon, his commentary on the Book of Daniel, “Since my youth… the Holy King has brought me to the gates of the Law, and there my Rock and Redeemer has placed me.” During the daytime, he occupied himself with the practical field of halacha, but after the sun went down, and the day’s clamor gave way to the pensive solitude of night, he devoted himself to intensive Talmudic study. “There are two ways a man can acquire his place in the World [to Come],” he wrote: either by immersing oneself in the study of G-d’s Torah, or by “caring for His people, inquiring after their welfare… and guiding the perplexed.” Evidently, the Alshich aimed for the former, but was destined for the latter.

In those years, the Ottoman Empire was still in its expansionary phase, and once it conquered the Holy Land in 1517, the soil of Eretz Yisrael began to beckon again. In the following decades, the competent governance of Suleiman the Magnificent brought both an improvement in material conditions in the Land of Israel along with a stream of immigrants, the Alshich among them.

Then as now, Diaspora dreams centered around Jerusalem. Nevertheless, most of the new immigrants flocked to Tzfat, perhaps because relations with the local population were more amicable there. What was for centuries little more than a sleepy village in the Upper Galilee, and without much Jewish history to speak of, was about to enter a period of explosive growth. In one scholar’s survey of the city, Tzfat had perhaps three synagogues at the start of the Ottoman era. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, it had twenty-one. Where there was perhaps one Talmudic college, some seventeen more had popped up, in addition to a large school for the poor, with 400 pupils and twenty teachers. In the second half of the sixteenth century, Ottoman records show there were 945 Jewish taxpaying families, and a slightly larger number of Muslim families.

Already in the first half of the sixteenth century, the town had a Greek, an Italian, a Portuguese synagogue, and more. New arrivals were expected to join a congregation of their countrymen, and each formed a community unto itself, with a shul, a yeshiva, and a preacher. An umbrella council called the Beit HaVaad, or Meeting House, was also formed, comprising heads of the various congregations and other unattached rabbis, and would assemble to discuss matters of importance to the general community.

It is believed that the Alshich arrived in town around the same time as Rabbi Yosef Karo, in 1536. Tzfat’s Golden Age had well and truly begun. The city now had such an extraordinary assemblage of world-class scholars that one, Rabbi Yakov Beirav, felt that the time was ripe to revive the practice of traditional ordination. Since it was disrupted in Roman times, the ancient ceremony of Semicha had been reduced to a pro forma rabbinical ordination that had lost much of its original judicial heft. Now, Rabbi Beirav formally ordained Rabbi Karo, and Karo in turn bestowed the Alshich with the power to grant Semicha to others. The words, “Ordained by Our Master [Rabbi Karo],” are today emblazoned over the Alshich’s resting place.

In time, the Alshich founded two Talmudic academies, became the rabbi of one of the town’s synagogues, climbed the ranks of the rabbinical court, and ascended to the Beit HaVaad. Between attending to his students, responding to halachic queries, and engaging in communal affairs, he could hardly spend his days sitting in Torah study as he once had. Meanwhile, in his position as a pulpit rabbi, he began to deliver public sermons in his synagogue. For him, the sermons were something of a sideshow. As Shimon Shalem writes: “His primary occupation was the study of Jewish law… he delivered homilies only out of necessity; his studies of Scripture, and the insights he produced therein were for their own sake.”

He charted a course between the exoteric and the esoteric.

As it turned out, the Alshich was an enormously popular orator. Every week, throngs of people would stream into his synagogue — from simple folk, to great sages like Karo and Luria — to hear him expound on the weekly Torah reading. He prepared the sermons on Shabbat Eve, spoke on Shabbat, and then sat down to write the next day, or that evening, once it was permissible to do so. His great printed works later emerged from these notes, beginning with Chavatzelet HaSharon in the 1560s (mistakenly thought to be the first book printed in the Holy Land; in fact, it was printed in Constantinople). The centerpiece of these writings, which came to cover almost every part of Scripture, is his commentary on the Torah, which the Holy Alshich rather grandly titled Torat Moshe — the Torah of Moses.

Crypto-Kabbalism

In his sermons, the Alshich did not dwell on the literal or legal meaning of the passage in question, nor analyze it solely through the mystical lens of interpretation for which Tzfat was known. Instead, he charted a course between the exoteric and esoteric. He would begin his exposition with a barrage of questions, and then, as he went about resolving them, focus on the moral and spiritual lesson to be derived from the text. Generally speaking, there are four basic genres of Scriptural interpretation, and the Alshich drew upon them all. Along with the literal (P’shat) meaning of the Torah, he used allusory (Remez) and mystical (Sod) references as well, but the Alshich specialized in the method of homily, or D’rush. Thus the Alshich is famous as the Darshan par excellence.

Although Rabbi Luria attended the great Darshan’s lectures, according to some accounts, the Alshich did not return the gesture. This was not, however, for a lack of effort or desire — far from it. In his encyclopedic Shem HaGedolim, the Chida, an eighteenth-century Jerusalemite scholar and sage, writes that the Alshich sought to study Kabbalah together with the Holy Ari and his inner circle of students, but was rebuffed. The Ari’s explanation for this was nothing short of extraordinary: Souls are sometimes sent into this world to teach it something new, or to reveal a new facet of the G-d’s wisdom, as expressed through the Torah. The Alshich, who the Arizal’s disciple Rabbi Chaim Vital later said was a reincarnation of the Talmudic Sage Ravina, had come into the world for the sake of Drush. In other words, according to the Ari, the Alshich had already found his calling in the world of homily.

At the same time, the notion that Alshich did not engage in the study of Kabbalah at all is a mistake. The Zohar is cited numerous times throughout his writings, alongside other more oblique references to the “Hidden Wisdom.” Shalem writes that Kabbalistic ideas are foundational to the Alshich’s worldview, from “the structure of the worlds, the nature of the soul and of man, to the rationale for the commandments, rewards and punishment, and . . . the fundamental principles of faith.” Studying mysticism and the inner dimension of the Torah, he believed, was the highest form of Torah study, and he encouraged others to engage in it as well. Still, he firmly argued that basic Jewish practice could not be neglected in favor of Kabbalah study. In a memorable passage, he writes that one who engages only in mysticism is like –

“The astrologer, who walks across the earth under the darkness of night. As he strolls, he gazes heavenward, to the stars, and does not turn to the earth below, or to the tread of his feet. He will surely fall into a pit, or through some other gap that he does not see.

The same will happen to someone who places all his attention and the length of his days to mystical matters above, without giving a proper share to studies that lead to the practical, to distinguish between the prohibited and the permitted. Will he not surely fall, in his ignorance of the Torah’s strictures, as he makes his way in the dark?”

Some have suggested that the Alshich presented a kind of “Kabbalah-lite,” popularizing for the masses mysterious ideas once whispered in the quiet corners of Tzfat.

Thus, Alshich’s teachings were fully in conversation with every part of Torah, and consonant with ordinary life. Although he wrote in flowery and elaborate prose, his discussion of esoteric ideas is free of jargon. Because of this, some have suggested that the Alshich presented a kind of “Kabbalah-lite,” taking mysterious ideas once whispered in the quiet corners of Tzfat and popularizing them for the masses.

The Ari famously declared of Jewish mysticism that “in these latter generations, it is permissible, and a duty, to reveal this wisdom.” Yet the Ari had a highly exclusive coterie of initiates, and his teaching tenure in Tzfat was blazingly brief: As tightly as his name is bound to the city’s, it is easy to forget the remarkable fact that he only lived there for two meteoric years, before passing away at the age of 38. Not many could gaze at his star directly. Thus the Alshich and disciples like Rabbi Chaim Vital were instrumental in ensuring that the Ari’s light — the inner light of Torah — actually reached the people.

Proto-Chasidism?

As the Alshich grew old, the Golden Age of Tzfat drew to a close. The city was hit by an economic downturn, and a plague that forced the Darshan to leave the city for a while. He also turned his hand to raising funds for the city from abroad. Eventually he returned, and passed away in Tzfat in 1600 (although, as with regard to his birth, some quibble with this timing). In that same year his magnum opus, Torat Moshe, was printed, and has remained an essential part of the Jewish library ever since. The Alshich’s writings on the Torah proved especially popular among the Chasidic masters who emerged some two centuries after his passing, and also extended the esoteric dimension of Torah to the masses – and to everyday life. Rabbi Yakov Yosef of Polnoye and Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, in particular, frequently cite him in their writings.

This brings us back to the Alshich’s shul, and to another special bond between the Darshan and the masses that seems to anticipate the Chasidic movements he so influenced.

After miraculously surviving the earthquakes that devastated the town in 1759 and 1837, the Alshich’s shul is in fact the only structure from the Golden Age still intact. Over the years, it has had different names: Knesset Yechezkel, after a sponsor of its nineteenth century renovation, and Kenis el Istambulia, since many of its original congregants came from Istanbul. Back in the day, it had another name as well: The Synagogue of the Baalei Teshuvah — the Penitents. As the story goes, the shul was also home to some of the Spanish conversos — Jews who were forcibly converted and stayed behind after the Expulsion. Once they returned to the faith of their fathers, in the Holy Land and elsewhere, there were those who were hesitant to receive them. Having lived as Christians for so long, should they be readmitted to the synagogue and permitted to study the Torah along with everyone else?

Centuries before the first Chabad House, the Alshich said yes, and opened the doors of his shul to the Penitents. In fact, some of them are said to have been involved in its construction. There they would sit each Shabbos — sandwiched, we can imagine, between the illustrious author of the Code of Law, Rabbi Yosef Karo, and the Holy Ari. For the Alshich, the Torah and her secrets ought to be available to every Jew.

Our people have been blessed with many great sages, but very few have the honorific “holy” attached to their names. The Holy Moshe Alshich, the Holy Ari, and only two or three other figures in Jewish history are referred to as such. At first, given everything we know about the Alshich, this might surprise. After all, the word kadosh, holy, generally implies some degree of separateness or remove — hardly a trait one would associate with a popularizer and preacher with the mass appeal of the Alshich. But holiness is also everywhere around us, is it not? The Alshich’s holiness, one might say, was not of detachment or of exclusion, but of sacred immanence.

Be the first to write a comment.