Tehillim, Book of Psalms: With commentary from the Talmud, Midrash, Kabbalah, classic commentators, and the Chasidic Masters

Compiled by Rabbi Yosef B. Marcus

Kehot Publication Society, 696 pp., $59.95

*****

Why read Tehillim? Psalm 22 read self-referentially with the insights of the new Kehot Tehillim can shed some insight on this question.

“For the Conductor, on the ayelet hashachar, a psalm by David. My G-d, my G-d, why have You forsaken me? Why are You so far from saving me, from the words of outcry? My G-d, I call out by day, and yet You do not answer; and at night—but there is no respite for me. Yet You, Holy One, are enthroned upon the praises of Israel. In You, our fathers trusted; they trusted and You saved them. They cried to You and were rescued; they trusted in You and were not shamed. Yet I (the Jewish people in exile) am a worm and not a man; the scorn of men, the contempt of nations. All who see me mock me; they open their lips with derision; they shake their heads with scorn. But one who casts his burden upon G-d—He will save him; He will rescue him for He desires him. . .” (Psalm 22:1-10)

This psalm begins with an expression of despair in one’s prayers being heard, and then transitions to a description of those who nevertheless trusted in G-d, despite difficult circumstances, and were answered. It invites the reader who feels a sense of hopelessness to dig deeper within, and to elicit salvation through one’s strength of faith.

The Kehot commentary on this chapter provides additional insights that deepen this theme. The ayelet hashachar is an instrument that begins softly, gradually rising in volume like the rising light of dawn. The commentary further notes that the word for dawn in Hebrew (shachar) evokes the word “shachor”—darkness, for darkness creates the desire for light. It is from darkness that dawn is born.

The ayelet hashachar is also an allusion to Queen Esther, the beautiful “morning doe” who brought light and salvation to the Jewish people, like the dawn breaking through the night. When Queen Esther was told by Mordechai that Haman had plotted to kill the Jewish people and that she should enter the presence of the king uninvited in order to intercede on their behalf, she did as he requested, despite her reservation. As she entered the antechamber of the room, the Divine presence left her. In despair she cried, “Why have You forsaken me?”

Yet the cry of despair is then channeled inward. G-d seeks the praises and prayers of Israel, if they come sufficiently deep from within. If they are offered sincerely and with faith, then they will undoubtedly be answered. The dark will turn into light; the low tones of the ayelet hashachar will rise to a crescendo of beautiful sound and deep emotion.

******

A couple of years ago, the daughter of Holocaust survivors told me, “My parents were part of a generation that still talked to G-d.” Sometimes angry, sometimes pained, sometimes grateful, sometimes pleading—they would address G-d directly, in constant conversation that signaled the depth of a relationship that was palpable and real.

Though throughout the ages people have spoken to G-d in their own words, when they sought a text to give expression to their longing to connect, the text they most often turned to was the Tehillim, the Book of Psalms. There are psalms that give voice to expressions of hardship and sorrow, as well as psalms that express joy and thanksgiving. The Rebbes of Chabad strongly encourage the daily recitation of a portion of Tehillim, and it is commonly recited in other Jewish communities as well.

A story is told about the wife of the third Lubavitcher Rebbe (the “Tzemach Tzedek”) whose sons once heard her reciting Tehillim with many errors. They corrected her reading, and she approached her husband and asked if perhaps it would be better if she stopped reading the Tehillim since she did not always say the words correctly. The Tzemach Tzedek chastised his sons for correcting her, telling them that it was in the merit of her Tehillim that brought him success in his missions and averted much disaster.

While a different generation may have naturally poured out their hearts as they read the words of Tehillim, in our time, many find it more difficult to engage in that kind of a relationship. The new Kehot Tehillim, however, can be an invaluable aid to making the recitation of psalms a more meaningful experience.

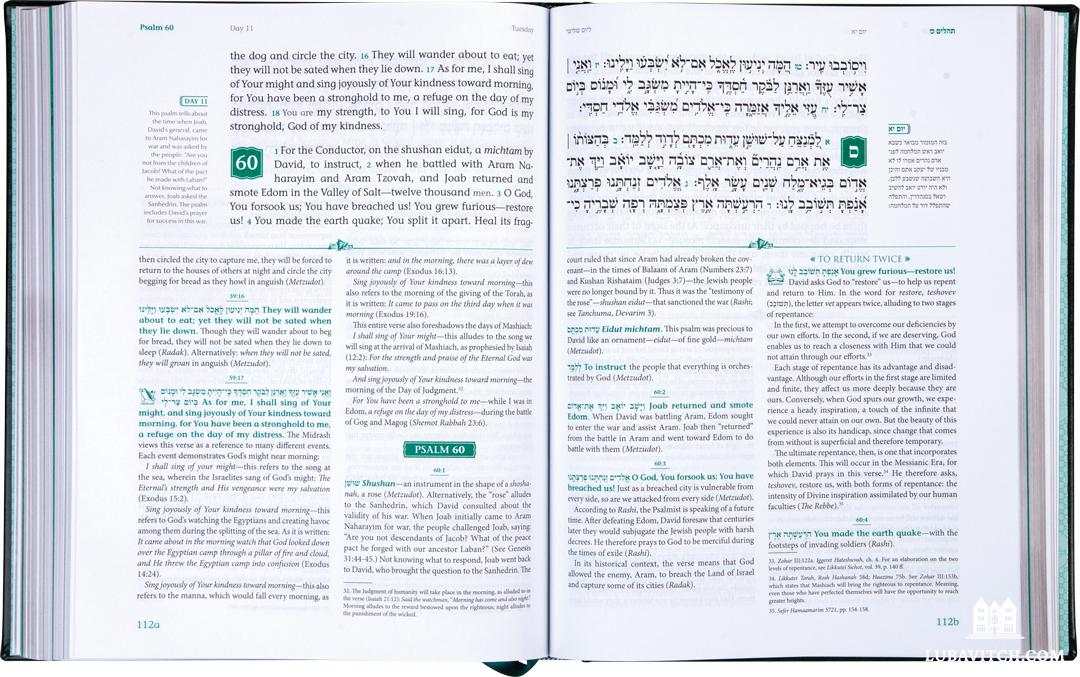

Published in an 8.5 x 11 format with gilded pages and a beautifully embossed, sage green cover, you will not take the Kehot Hebrew-English Tehillim along with you in your purse to read on the train. It is hefty, serious, with clear print and generous use of white space that is restful to the eye. This is a Tehillim to read in your living room in a format that encourages thoughtful recitation and quiet reflection.

The translation itself appears to be adapted from the Tehllim Ohel Yosef Yitzchak used by Kehot (which was also edited by Rabbi Marcus). A notable new feature in this edition is the interpolation of words to help clarify the meaning of the text. For example, Psalm 1:6 reads: “For G-d pays attention to and blesses the path of the righteous—whereas the path of the wicked shall perish.” Similarly, Psalm 37:5-6 reads: “Better the little of the righteous than the abundant wealth of the wicked. For the arms, i.e., strength of the wicked will be broken and their wealth lost; but G-d supports the righteous and they retain their possessions.” The interpolations are generally sparing, but they are helpful in making sure that a contrast or comparison is correctly understood.

The commentary is carefully selected and helps place the Tehillim in a larger ethical context, and illuminate it with the Chasidic perspective. For example, Psalm 24:3-4 reads: “Who may ascend the mountain of G-d and who may stand in His holy place? He who has clean hands and a pure heart, who has not taken My Name in vain or sworn falsely.” The commentary notes that this seemingly repetitious phrase refers to two oaths: the oath administered to the unborn child to be a righteous person, as well as the oath we took at Sinai to enter a covenant with G-d. Thus, the chapter is not talking only about “telling the truth,” but about remaining loyal to our essential mission in this world.

Some minor defects mar an otherwise beautiful and resonant book. The directionality of the pages in the index feels idiosyncratic; there are some subtle inconsistencies in the grammar of the translation; there are occasional references in the footnotes that raise issues for the uninitiated reader that are not adequately dealt with. I hope that in future editions, these issues will be addressed. Still, for everyone who regularly recites Tehillim (or is ready to start), this is a book that will considerably deepen—even transform—the experience.

******

The Editor Asks the Redactor: Questions for Yosef Marcus by Baila Olidort

Traditionally, we relate to Tehillim as prayers. Why turn it into a study text?

Yosef Marcus: When Kehot approached me about doing a commentary on Psalms, my reaction was exactly that. I had not thought of Tehillim as something to study. But after several years of studying Psalms, I have a new appreciation for it. In the introduction, we address these two aspects of the Tehillim that make it unique within the Tanach. As the Rebbe once put it to the author of a compilation of commentaries on Tehillim: In prayer, we engage our hearts in pursuing the Divine; in Torah study, we engage our hearts. Tehillim is unique in that it contains both.

The 150 Psalms often don’t seem to follow a particular theme but read more like a collection of poetry. Do you see a unifying thread or theme?

Yes, that is definitely the sense one gets. On the other hand, there are a number of commentators who ascribe a theme to each of the Five Books of the Tehillim (which correspond to the Five Books of Moses, incidentally). We cite a few approaches in the introduction.

What surprised you most in your research?

I was surprised by the immense amount of actual laws and customs that are derived from Tehillm. That certainly did not fit the image I had of Tehillim as a book of prayer and simple faith.

The new work is an anthology of many classic commentaries on Tehillim. What are the different approaches these various commentaries take, and which was most compelling to you?

We can categorize the commentators into some basic groups. The first is the “pashtanim,” the commentators who provide a straightforward, “simple” exposition of the verse. These include: Rashi, Ibn Ezra, Radak, Metzudot, and others.

The second group includes Rabbi Moshe Alshech and Rabbi Yosef Yaavetz. These rabbis lived in the 15th and 16th centuries, several centuries after the “pashtanim,” and their approach is often based on Kabbalah. I don’t mean the esoteric or cryptic aspects of Kabbalah, but to certain Kabbalistic principles, such as the “exile” of the Divine presence, something that Alshech comes back to many times, or the idea of making a “home” for G-d in this world.

Going back approximately two thousand years, we find the Midrashic commentary. The content and style of the Midrash is soul-stirring. It’s remarkably raw in describing the connection and love between G-d and the Jewish people. I found this very compelling.

Most compelling, however, for me, is the Chasidic commentary, mostly from Chabad literature.

What is there in the Tehillim that might resonate with the modern-day reader?

Modern humans suffer a great deal of anxiety. We are the generation with the most things but are the least happy. The themes of Tehillim—faith and trust in G-d, gratitude, hope, etc.—are a balm to today’s overstimulated and spiritually undernourished soul. The fact that these teachings were lived by the author, King David, provides the reader with a human model for these ideals.

What criteria did you use in selecting the commentaries you did, and what sets this one apart from other works on Tehillim?

As with our earlier commentaries in this series published by Kehot—Ethics of the Fathers and the Haggadah—our goal was to provide a well-rounded commentary. We start with the classic “pshat” commentators for the basic understanding of the text. That is the foundation upon which we can then layer the Midrashic, Talmudic, and Chasidic insights. This is the first commentary that I know of with this level of breadth.

What were the challenges unique to this project as compared with Pirkei Avot and the Haggadah, which you worked on?

Because Tehillim is written in poetic language, the verses are often cryptic and unintelligible to the point where most yeshivah graduates may not be able to translate many a verse without resorting to commentary. So it was a struggle to merely understand the plain meaning of the text, something that was not an issue with the other projects. The translation and interpolation were extremely difficult to do. Another challenge was the sheer length of the Tehillim. I like to see the end in sight when working on a project, and I did not have that luxury in this case. Eventually, I made my own goalposts (finishing five Psalms at a time) and that worked very well.

Be the first to write a comment.