Purim celebrates a familiar plot: A nation threatened with destruction is saved at the eleventh hour when its enemy’s plans are miraculously thwarted. Deliverance comes through Esther, introduced to us in the Megillah as a young, shy maiden, at first, unprepared when called upon by Mordechai to take action to save her people from annihilation.

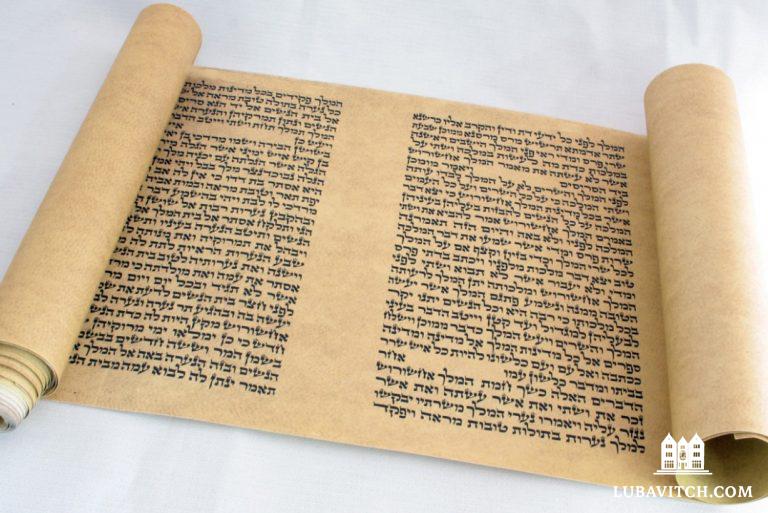

The Baal Shem Tov teaches us that if we read it as a historic document without regard for its immediate relevance, we have not fulfilled the mitzvah of reading Megillat Esther on Purim.

In a way, we can read Esther’s story as a paradigm of the “evolution” of the traditional Jewish woman of our own day. We asked women in leadership to share some of the salient points in the Story of Esther that are instructive to them in their own lives.

Reluctant Hero

Sarah Alevsky

The Megillah describes Esther as a passive player. Taken to the palace against her will, she does not “divulge her nationality or lineage” until instructed to do so by Mordechai. She seems to have accepted her situation as fate, and we see no indication of her trying to change her circumstances. When Mordechai inquires about her, he asks, “And what is being done to her?”

True, we know that there wasn’t any recourse for her as a woman in the male-dominated world of ancient Persia. We only have to look at the way in which Queen Vashti unwittingly engineered her own downfall by defying the king.

But this changes when Mordechai makes her aware of Haman’s plot to destroy the Jewish people. Initially, she questions Mordechai about the logic of her approaching the king; anyone who enters his presence unbidden will be killed, “and I have not been summoned for 30 days.” Perhaps she has lost favor with Ahasuerus and if so, there is slim chance that she will succeed.

In response, Mordechai says, “Don’t imagine you alone, from all the other Jews, will escape by being in the palace. Actually, if you remain silent, the Jews will find relief and safety through a different route, while you and your father’s house will be lost!”

Powerful, even harsh words from Mordechai. He knew that salvation would come to the Jewish people, but he tells Esther to consider her own fate. Then he adds the kicker: “And who knows, perhaps the monarchy came your way precisely for this moment?”

With this, Esther appears to transform. She becomes a woman of action. She tells Mordechai to instruct all the Jewish people to fast for three days, and she and her maidens fast as well. And then she will brave the threshold of the King’s throne room, come what may: “And if I will be lost, I will be lost.”

This last line is sung by the reader in a dirge-like lament: I know I am going into a scenario where I have no idea how it will turn out, but I am doing it because my people have no other champions, and I must take this risk now.

From this point, things don’t happen to Esther; she makes them happen. She enters the throne room, she invites the king to a series of private parties with his trusted advisor, Haman. And at the right moment, she accuses him of plotting to destroy her and her people, arguably the climax of the story.

Esther was a reluctant hero. She wasn’t a bold warrior rushing into battle, come what may. She was not Yehudis, who calmly sauntered into a general’s tent and beheaded him, nor was she Devorah, who exhorted the Jewish nation to fight under Barak. She simply was trying to make the best of her situation.

We as women often prefer not to make waves. We are even willing to suffer in silence so as to avoid confrontation. But as mothers, we are genetically wired to protect our offspring. Threaten our children, and we become tigresses. Although confined inside the walls of the palace, not free to live as she wanted, Esther’s response to the plight of her people was fiercely maternal.

Things happen to us that are beyond our control. We may feel stymied or frozen. But as women, we need to draw upon our feminine skills to take initiative, to recognize and act on the opportunities that present themselves to us when the future of our people, our children, is at stake.

Sarah Alevsky heads the Chabad Hebrew School and the Kivun after-school program at Chabad of the Upper West Side. Co-director with her husband of Chabad Family Programs of Chabad of the West Side, Sarah is passionate about creating Jewish educational experiences that challenge and inspire Jewish children and their families.

Prosaic Heroism

Rivka Denburg

In learning and teaching the Megillah, two things stand out for me. The first is the understanding of how long a period of time the Megillah story actually covers. The second is the seemingly irrelevant nature of the final chapter of the Megillah.

For one unknowledgeable about the details of the Purim story, events seem to fly thick and fast, yet in reality, there are months and years of ordinary existence in between. In reading the text one sees that the party began in the third year of Ahasuerus’s reign, lasting six months. Esther became queen in the seventh year, after the one-year regimen of beauty treatment prior to entering the contest. And it wasn’t until five long years later, in the twelfth year, that Haman began hatching his plot and Esther was called upon to actualize the potential inherent in her high position in the king’s palace.

The second point is the last chapter, consisting of three verses regarding Ahasuerus’ internal policies, including a tax that was levied. What an anticlimax! The previous chapter concludes on a high note of celebration, and recognition of the miraculous turn of events. And then: And King Ahasuerus imposed a tribute on the land and on the isles of the sea. Is this the follow-up to a stunning and triumphant chain of events?

Yet if the end is the summation of the entire concept, then these details of tedious time and taxes must be relevant to the more dramatic and heroic aspects of the story.

So where does that leave me and my students? Actually, right in the thick of things. Because these two points emphasize the fact that heroes are not found in fantasy realms or public fanfare. Rather they arise in the needs of ordinary life, where taxes are collected and bills have to be paid, where ordinary jobs and chores form the basis of our interactions with others, and where petty crises crop up and a person is required to stand up and become a hero.

It may be more enticing to take a leading role in a dramatic situation, but Esther teaches me about the regality of maintaining your identity when no one is looking, and knowing who you are when day after day all those around you are doing something different. Throughout those years when the Jewish community was thriving in Persia, Esther was alone in the palace, with the task of accepting and carrying out Mordechai’s advice, to be quiet and prosaic. For Esther kept Mordecai’s orders as she had when she was raised by him. And when the war and the need was over, Esther went back, alone, to that prosaic world.

When routine, ordinary tasks seem to us to define the nature of our existence, Esther exemplifies how our essential existence, and the actions we choose within that framework, can define the everyday and mundane.

Rivka Denburg is Head of School at the Hebrew Academy Community School in Coral Springs, FL, where she and her husband have raised their children and established a Chabad outpost since becoming the Rebbe’s shluchim to the area 30 years ago. Rivka is involved in adult education and outreach.

Repairing Relationships

Aviva Deren

Campaign season in the U.S. evokes images of leadership that are so pervasive, it’s easy to think of them as universal. We readily take for granted that the office of power is power, and that that type of power is ultimately the strongest.

Purim offers a chance to use a different lens, to see things from a different perspective. The holiday swirls around the images, the story and the practices recorded in the Book of Esther. Even before we open the Megillah, its name provokes questions and deeper thinking.

Why was it named for Esther? To be sure, she is not the only major figure in the Megillah. What about Mordechai? The book could have been called the Book of Mordechai, or the Book of Mordechai and Esther, or even the Book of Esther and Mordechai. It would seem that the title itself was meant to convey a message, a value.

In a nod to the Purim tradition of costumes and masks, it is worth noting that the Book of Esther is itself a mask, the only book of the Bible in which G-d’s name does not appear–not even once. At the time, the majority of the Jewish people dwelled outside of the Holy Land, subjects of a foreign king, and the looming threat of destruction appears early in the story. Esther’s heroism is attributed to her dramatic appeal to the king to save her life and the lives of her people.

In a deeper reading, the classic commentaries see the Megillah as a chronicle of the relationship of the Jewish people and G-d; it is a troubled relationship. They see the story as it is told as an almost superficial reflection of a deeper and far more consequential narrative.

Viewed through this lens, Esther is indeed the heroine. But her breathtaking speech to the king is only the spectacular fireworks, a sideshow to the real story.

Esther (ranked among the prophets of our people) identified the core issue, and with it, the necessary solution. “Go gather all of the Jews . . . and fast for me, do not eat and do not drink for three days and nights, and I and my maidens will fast as well, and then I will go to the king. . . . ” (Esther 4:16)

The Megillah turns on these words.

Esther identified two classic ingredients of Jewish survival: the power of a united community and the value of individual (and subsequent communal) connection to G-d. So sure was she that these were the critical elements of success that she even convinced Mordechai, the leader of the Jewish people, to call for a fast day even though, according to the Talmud, it was the holiday of Passover. And Mordechai “did all that Esther had commanded him.” (Esther 4:17)

Mordechai symbolizes the timeless truth of Torah, and teaches the foundational values that are the core of Jewish life and survival. Esther symbolizes the ability to apply those values to the crises of current events, to see the larger picture and to zero in on what has to be done.

Ultimately, the drama of this story turns on the reconciliation of the Jewish people and G-d. Esther staked her life on this premise; it is the combination of her call to action and personal self sacrifice that earned her the singular honor of having the story carry her name.

Mrs. Shifra Aviva Deren is co-director of Chabad Lubavitch of Connecticut and Western Massachusetts. Aviva is the founding director of the award-winning Gan Yeladim Early Childhood Center in Stamford, CT. A speaker on the role of women in Jewish life, she is a much sought-after mentor.

marjorie spofford

very interesting