By the time twenty-year-old Emily Couch walked across the plaza to the ancient stones of the Western Wall, she was exasperated. Despite having no Jewish family and only a few Jewish friends, she somehow found herself desperate to become a Jew. Yet feelings of self-doubt had been growing stronger. Was she trying to fill a void and going about it all wrong? “I wasn’t sure if I’d lost my mind,” she says.

As she touched the stones of the sacred wall, Ms. Couch prayed, “G-d, if I don’t belong here, please take this feeling away; because if you don’t, I will go through with this, and that scares me.” She flew back to Cleveland and carried on with her college education, but the feeling wasn’t going anywhere. College was just background noise. After years spent with no clear direction in life, Emily was laser-focused on converting to Judaism. “I was on a runaway horse,” she says, “it was all so irrational.”

***

Growing up in a tiny town in rural Ohio, Emily’s parents left her with mixed messages about religion. Each Sunday her father drove the family to the same Catholic church he’d attended all his life, and during the week, Emily attended Catholic school. But her mother remained a Methodist at heart, and her father often ridiculed religiosity.

As she watched her classmates confirm into the Catholic faith in sixth grade, Emily knew she didn’t belong. “I told my parents it was not for me,” she recalls. Emily transferred to public school, where her isolation and loneliness only grew.

“It seems absurd,” Emily says, “but I looked around and felt I didn’t belong.” Feeling rejected and out of place, she saw the world as an awful place, and became angry at G-d. In high school, the young Ms. Couch committed herself to atheism. “I never entirely shook off my belief in G-d, but I envied the people who could be sure that there wasn’t one,” she says.

In particular, Emily mocked anyone who displayed any religious feelings. “I pushed everyone out of my life and decided that if I felt rejected, there was no reason for it — everything is chaos; just look at the world!” Hoping to drown out any residual faith inside, she saw a kind of freedom in atheism. “It meant I’d be free from those nagging questions,” she says. When a classmate told her, “you’re the most miserable person I’ve ever met,” it sounded like a badge of honor.

But anger takes energy, and she could feel a black hole growing inside. “Anger is fire, but I was the fuel.” By the time she narrowly graduated high school, Emily was out of fuel and burnt out. She asked herself, “Do you even know who you are angry at?” And then it dawned on her. “I had no idea who G-d even was!”

“I began searching, but I wasn’t looking for a spiritual high. I had locked spirituality out of my life.” She spoke to Satanists, neo-Pagans, and Christians of all stripes, She explored Eastern religions, and met people on unique journeys. She wanted to know why people believed what they did and why. “Most people were very open, and it was always an entertaining conversation,” she laughs.

But after all her exploration, Emily says, nothing called her name. “Every religion said something I agreed with,” she says, “but I wanted to devote my life to something worthwhile, and just agreeing with a religion wasn’t going to make me marry myself to it.”

Unable to find the spark she sought, Emily began aimlessly flipping through her history-major father’s countless books. Soon, she noticed a theme. “I realized, ‘Oh my gosh, what is happening with these Jews.'” Seeing they had never been a large group, she marveled that they had survived history despite many attempts to extinguish them. “I had to admit that I finally found something undeniably supernatural,” she says. “I didn’t decide then that I had to become a Jew. It was just that I knew I had to be a part of this people.”

After a brief stint in art school, Emily began attending Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. There, for the first time, she met rabbis and visited several temples and synagogues. When Ms. Couch learned of an Orthodox Rabbi who gave informal classes on campus, she showed up. After class one day, she walked up and told him she wanted to convert. At first, he rebuffed her a few times, but when he realized she was in earnest, he arranged for her to study with a rabbi from the Beis Din of Cleveland.

Emily made a few Jewish friends, and they surprised her by inviting her on a trip to Israel. “But I’m not Jewish,” she resisted. Still, they insisted, and off she went. By now, Ms. Couch couldn’t help but wonder if she’d lost her mind. The conversion process was dragging on, but this feeling that she had to become Jewish was propelling her. It was on that trip that she begged G-d at the Western Wall to either take that feeling away or allow her to become a Jew.

Eleven months later, with her hair still wet from the mikvah, a very Jewish Emily — now Rifka — stood outside on a sunny November day. “There I stood, a complete failure as an atheist.”

The following Shabbat, Rifka walked to an Orthodox synagogue near her apartment on campus. “I met nice people, but it was hard because I always felt a little out of place,” she remembers.

Rifka tried another synagogue each week, but when she trekked across town to a small Chabad synagogue in a storefront, she found the front door locked. Russian letters adorned the back door, but she walked inside. “It was loud,” she says, “I could hear Hebrew songs and people yelling in Russian, and I thought, ‘this is it!'” It was tiny. She sat down, and a woman turned around to introduce herself. “Hi, I’m Lois. Do you have a place for lunch?”

Rifka happily accepted, and from that week on, she walked forty-five minutes to the small shul, where Lois became her Jewish family. “I am blessed that the right people were there for me when I needed them,” Rifka says.

Rifka was about to graduate college with honors when she called home with news, “I’m not graduating. I’m moving to Brooklyn.” She wanted formal Jewish learning and signed up for a year at Machon Chana, a seminary in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood geared for Jewish returnees. At 1:00 am, she caught a Greyhound bus to New York for an experience unlike any other. “It was tremendously fun,” she says, “I made friends with amazing people from all around the world.” But from the start, it was clear Crown Heights operated “from a different owner’s manual,” and it often seemed it was all held together by an unreasonable amount of cheerfulness.

Rifka explains she had never come to Judaism looking for feelings of closeness to G-d. “I didn’t have any time for spiritual growth,” she says, “to me, that seemed silly.” And she still had a hair-trigger response whenever people displayed emotion towards G-d or Judaism. “For me, Judaism was about duty, ‘I’m a Jew, so this is what I’m going to do,’ it didn’t bother me that I didn’t feel anything emotionally, and I was still a cold person.” Still, she loved the people in Machon Chana and enjoyed the learning.

As the seminary year wound down, she was sitting in the basement with friends, drinking coffee and chatting, when the payphone rang. “Does anyone want to teach?” the caller wanted to know. When nobody else volunteered, Rifka thought, “that could be an adventure.” As it turned out, she had an absolute blast. On her first day at Beis Rivka High School, the sound almost knocked her over when she opened the door. “Girls laughing, yelling, and singing, it was the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen,” she laughs, “it was pure life all bottled up about to explode.”

While teaching that second year in Brooklyn, Rifka met a soft-spoken professor’s son turned yeshiva student named Shalom Chilungu. When they got engaged, her students at Beis Rivka surprised Rifka by fundraising for her wedding expenses and outfitting the young couple’s new apartment. “I don’t know where my class of 2004 is now, but they will forever have a place in my heart,” Rifka Chilungu says.

The Chilungus lived in Brooklyn, then in Cleveland. They welcomed four children into their family before settling in Rochester, New York, where Shalom Chilungu is an assistant professor of neurology and a neurohospitalist at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Raising a Jewish family, Rifka felt the cold intellectualism that had always defined her relationship with Judaism begin to thaw. “I saw my kids growing up, and I want them to love G-d,” she says, “I can’t possibly transmit that to them unless I can feel a warm connection to Judaism myself.” She realized it wasn’t only for her children, asking herself, “Don’t you think there’s also more in it for you?”

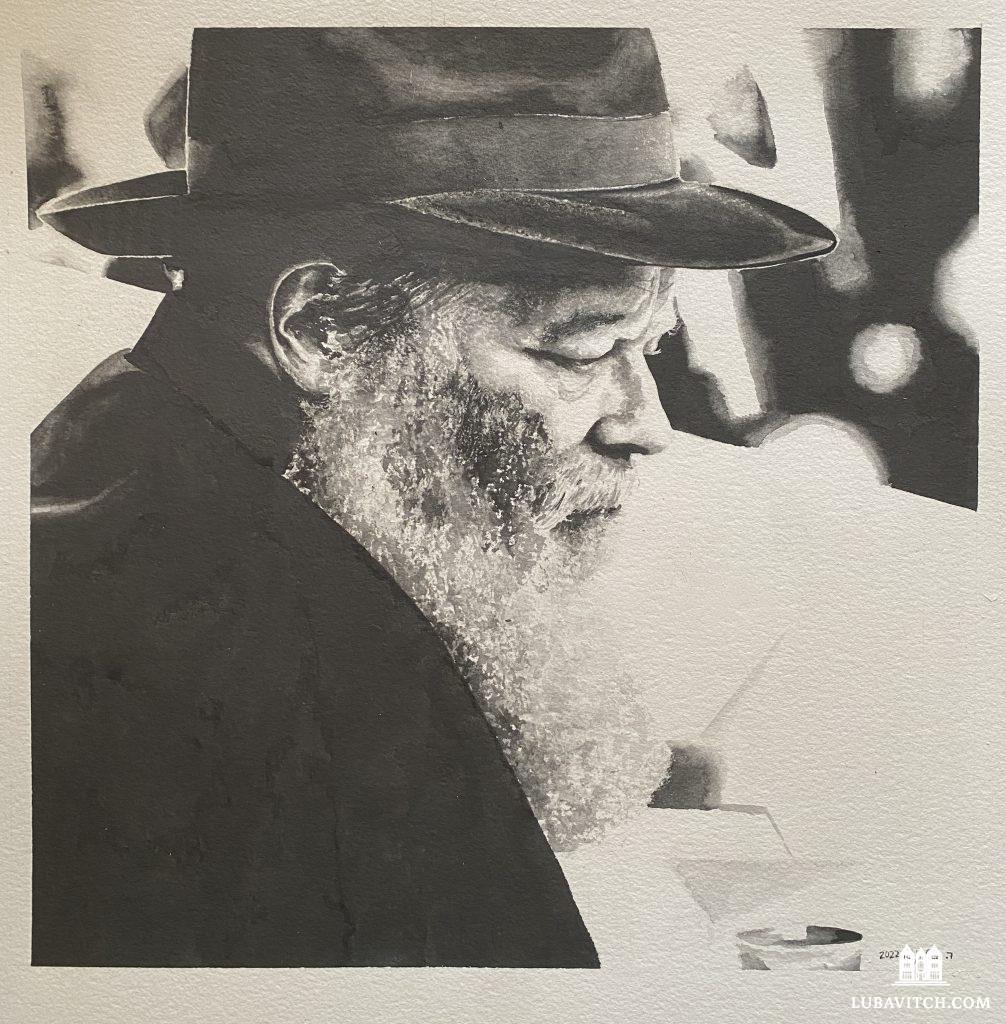

“It’s hard because you never want to be a fool,” Rifka says. “It sounds petty, but it can be scary to let yourself feel that connection because, ‘what if I’m wrong?'” So on the advice of her old mentors from Machon Chana, she began to learn Chabad Chassidus, always a passion of her husband’s. Rifka listened to audio classes online, and to help her focus, she sketched in a notebook. Soon she was creating full-blown art, and now she teaches art in a local school and occasionally to friends.

“That’s been the project for the past few years,” she says, “allowing my guard down enough that I can feel emotion towards G-d, instead of viewing him as some distant being.” As Rifka has grown more comfortable with an emotional Judaism, she looks back on her seminary year differently. “There was a wonderful rabbi who taught a Chassidus class every morning,” she says, “I never attended, but now I wish I could apologize.”

For Rifka, part of this project means sharing her story. When a mentor advised her to help others, she was unsure how to proceed. Soon after, she was asked to speak publicly about her story and thought, “maybe this will help someone.” Nervously, she agreed. Today, she talks and writes about her experiences for Jewish audiences.

Patty Arnold

Rivka, your life story is truly amazing. You are a blessing in this world and an inspiration to others. You have a beautiful family. Thank you for sharing! Baruch Hashem.

Eliezer

May you and you husband and children enjoy many years of happiness together.

Jo Warren

Very nice story, well written, a joy to read. The author has a way with his words. Wonderfully written.

A true admirer

Such a story was only done it’s true justice, by being told through the words of such a skilled storyteller. Yoni, you knocked it out of the park!

Rochel

Your journey is so inspiring! You and your family should see all the brochas in a revealed way. Never give up!! Only go forward!!

Kimberly Martin

You are inspiring. Thank you

Sarah

Hey I remember you! Wow what a journey. Your art is incredible! You can feature it in the Jewish Art Calendars!

A local Cleveland heightser

Eduard Fimblatt

Many Blessings to you, your husband and children.