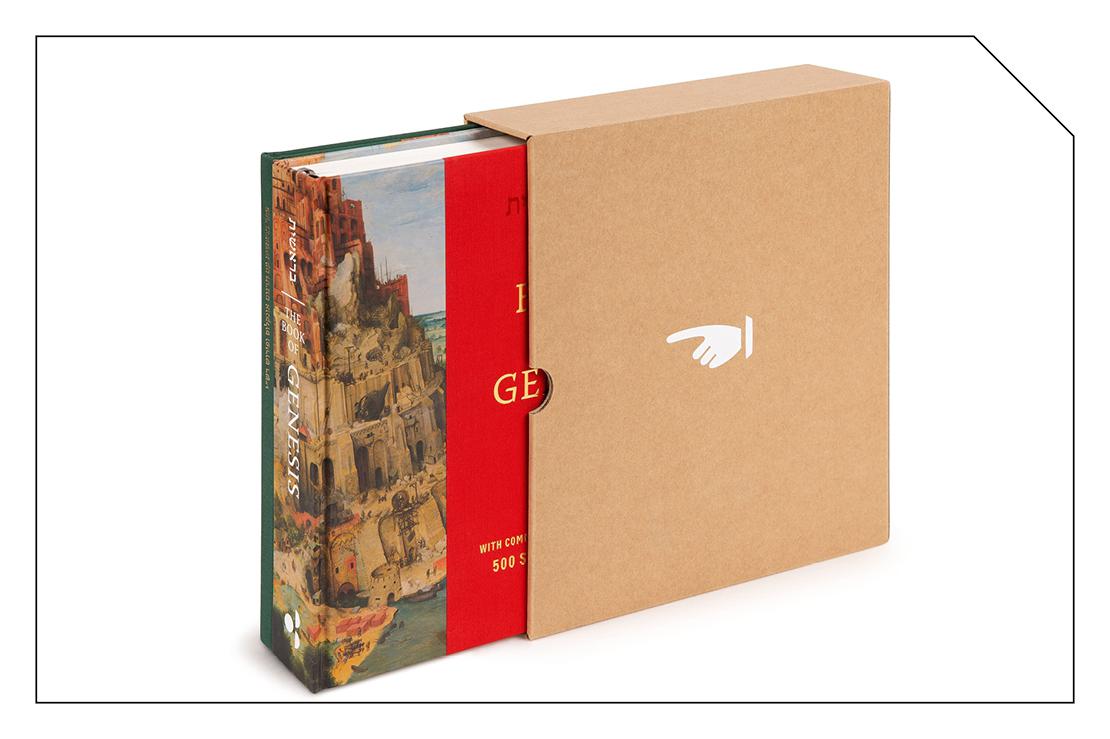

The Book of Genesis with Commentary and Insights by 500 Sages and Mystics

Compiled by Rabbi Yanki Tauber

Creative Design by Baruch Gorkin

Open Book Press

How does an ancient book find its way to our soul in a world overloaded with information?

Hypertexted and AI-driven, the Internet provides an avalanche in response to our every query. But, like sailors stuck in the horse latitudes with water everywhere but nary a drop to drink, we often go thirsty for meaning.

One response is to go back to the beginning. As Jews around the world begin the yearly cycle of Torah readings this autumn, a new edition of the Book of Genesis, Sefer Bereishit, invites us to engage more deeply with this fundamental text—and the ongoing conversation it generates.

The text, in a new translation by the compiler, Rabbi Yanki Tauber, is divided by the Torah portion. Each portion is prefaced with a synopsis, followed by a lengthier introduction and an overview that prime the reader for what follows. Among the strongest features of the work, the introductions go for the soul of the story, the layering of narrative and meaning that characterizes much of Genesis.

In the very first parashah, for instance, the introduction points out that although Genesis is indeed a story of beginnings, below the surface runs a narrative of false starts. The expulsion of Adam and Eve, the great flood, and the repeated pattern of familial strife in which elder sons are replaced by younger all seem to prove, Rabbi Tauber notes, that “the first fifteen centuries of human endeavor have been one colossal failure.” He then takes us deeper, pointing to the essential divine aspiration in Creation—-the turning of the self back to G-d that is called teshuvah—-which is capable not only of redeeming the false starts, but of realizing a perfection that could not be achieved any other way.

From these introductions we are drawn into the text itself and the commentaries.

First, a word on the translation: The aim of most biblical translations has been to make the text as comfortably idiomatic in English as possible. This is true not only of the non-Jewish tradition—the King James Bible is one of the great works of English literature, even when we Jews object properly to the agenda-driven choices that it occasionally made. It is true of much of the Jewish tradition too, from Maimonides to the Jewish Publication Society.

Rabbi Tauber’s translation, however, takes another approach. Using the text as a foundation, a jumping-off point in the ongoing search for meaning, it prioritizes the feel of Hebrew’s rhythm and syntax over fluency in English. This approach occasionally challenges the reader with coined words (“A fruitious son, Joseph” [49:22]), seemingly nonsensical phrases, and decidedly unidiomatic English, as when Abraham declares “I and the lad will go till like so” (22:5). While it may lack the accessibility and literary sensitivity of contemporary translations like those of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks and Robert Alter, Tauber’s Genesis evinces a deep respect for the text as it is, without adornment, as a source of profound and multifaceted meaning. And it achieves its aim: to pique the reader’s curiosity, sending us on a journey that will delve deep into the Jewish interpretive tradition.

As promised, Tauber gleans insight from more than five hundred commentaries, from biblical times through the twenty-first century, with no era lacking plentiful representation. The commentaries come from a range of perspectives, including the non-canonical Ben Sira in antiquity, diverse forms of rabbinic writing in the Talmudic period, Orthodox scholars using academic methods in Europe and America, and the renewed scholarship of the Land of Israel in all its richness.

Among the strongest features of the work, the introductions go for the soul of the story, the layering of narrative and meaning that characterizes much of Genesis.

Tauber’s erudition gives us access to a varied menu of thinkers. The world of a medieval rabbi in Spain differs from that of a Polish rebbe in the eighteenth century; neither bears resemblance to the experience of a Talmudic sage living in Sasanian Persia. Of course the bulk of the commentators quoted lived in times that were much different from our own, and their tacit understandings may occasionally strike us as alien. Rather than apologizing for this, or soft-pedaling the differences, Rabbi Tauber has chosen to let us feel the partiality and the difference.

Here, for instance, is a joined pair of commentaries spanning the centuries, illuminating the story of Abraham’s servant Eliezer, sent on a mission to find Isaac a wife. He prays to succeed (“G-d the G-d of my master Abraham please make happen before me today . . .”), and his prayer is answered. The core text (24:15) reads:

And it was that he had yet to finish speaking and here Rebecca was going out she who was born to Bethuel the son of Milcah . . .

The first commentary brought here is that of the second-century mystic Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who tells us, “Three people were answered by G-d as their words left their mouths: Eliezer the servant of Abraham, Moses, and King Solomon.” A fascinating context that prompts the question: what ties three people as diverse as these together?

The next commentary provides an answer. Spanning a 1,700-year gap, and giving a dizzying sense of the story’s perennial relevance, the Lubavitcher Rebbe asks, “What is the common denominator among the three petitioners? All three involved the fusion of opposites.” The Rebbe goes on to develop that idea, connecting these diverse figures and highlighting their fusion of multiplicity and oneness, a theme that underlies much of Genesis.

Not all the commentaries follow such a coherent thread. If there was a method—some criteria—by which the compiler selected the commentaries, it is unclear. Indeed, some do not immediately provide a deeper understanding of the text. Consider for example, the verse, “And Isaac sent Jacob and he went to Padan-Aram; to Laban the son of Bethuel the Aramean the brother of Rebecca the mother of Jacob and Esau” (28:5). It seems rather straightforward, yet Tauber saw fit to include Rashi’s comment on the words “the mother of Jacob and Esau”: “I do not know what this teaches us.” In this case, commentary on the commentary would have been helpful.

In other places Rabbi Tauber extends his trust in the reader a little too far. Given the focus on its English translation, one assumes that the book is intended for those who may be new to the study of Torah. Yet, when confronted with midrashic commentaries that stretch the bounds of logic or abrade the sensibilities of a modern reader, he steps aside and allows us to swim, or sink, on our own.

Some of these omissions are remedied at the end, however. The Book of Genesis concludes with a long section of appendices, which provide context and help to organize the story, and which serve as a first step toward future research, as surely many readers will be inspired to do.

For Genesis turns out not to be limited to its text alone. The organic and complete Bereishit lives rather in the minds of those who wrestle with its meaning and its Author. With its superb and intuitive design, this volume invites the reader to join in this creative, soul-deepening, thirst-quenching conversation. It will require time and thought to access it meaningfully. But the effort is worthwhile.

Be the first to write a comment.