It’s Wednesday afternoon and young men are streaming out of the yeshivah on Brooklyn’s leafy Eastern Parkway. Armed with snacks, crafts, and sheafs of paper, 180 instructors head to 90 public schools around New York City. They’re calling out last minute instructions to each other as van doors slam and engines rev up. The light changes and they’re off, bringing an hour of Judaism, Released Time-style, to all five boroughs.

Released Time is an offshoot of the National Committee for the Furtherance of Jewish Education (NCFJE). Their “Jewish Hour,” as it’s often called, was instituted by the Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, in 1941. In 1952, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that children of all faiths were entitled to an hour of religious instruction (or “released time”) during the latter part of the school day. As long as classes occured off public grounds and the schools were not involved in coercing or instructing students, Zorach v. Clauson confirmed the legality of the weekly lessons. Now approaching its 88th anniversary, Released Time proudly counts one million Jewish children as its alumni.

As much as the organization has grown over the decades, its goal has never been to max out membership. “I tell the instructors during orientation, ‘this is an organization that we hope will self-destruct,’” says Rabbi Sholom Ber Hecht only half-jokingly. Hecht’s father, Rabbi J.J. Hecht, who founded the NCFJE, led the Released Time program in its early years. “Our intention has always been for children to transfer to Jewish schools,” notes the younger Hecht, today chairman of the NCFJE.

Released time students wear orange t-shirts to identify themselves; the back reads: “I’m a Jew and I’m proud!”

Released time students wear orange t-shirts to identify themselves; the back reads: “I’m a Jew and I’m proud!”

In the 1940s, many immigrant parents were accustomed to instructors offering religious education during the school day as was then common in Eastern Europe. When they arrived on American shores, they discovered a dearth of Jewish day schools, so most parents–even those from traditional homes–sent their children to public school. When Released Time offered an hour of Judaism at no charge, many of these parents rushed to enroll their children. At its peak in the late 1940s, 10,000 children were attending Released Time’s weekly sessions.

But with rising enrollment came opposition. There were those who objected to the perceived collusion between church and state. Others felt that Released Time was too successful and worried that parents would consider this hour a sufficient alternative to attending Sunday Hebrew School or yeshivah.

That was never the case, Rabbi Hecht insists. “The curriculum never duplicated Hebrew School classes,” he explains. Rather, Jewish Hour occurred in synagogue basements and sanctuaries, and instructors “encouraged their students to attend the congregation’s weekly Hebrew School.” Released Time offered students lessons about Jewish holidays and the development of the Jewish people, but intentionally left out Hebrew reading and writing. When the day school movement gained steam soon after, instructors encouraged their students to make that switch.

How does an hour a week translate into yeshivah enrollment? It doesn’t always. “Today’s volunteers understand that their responsibilities are much greater and far-reaching than just one hour,” Rabbi Hecht explains. “They are there to provide a broader scope of Jewish experience for the child and for his or her whole family.”

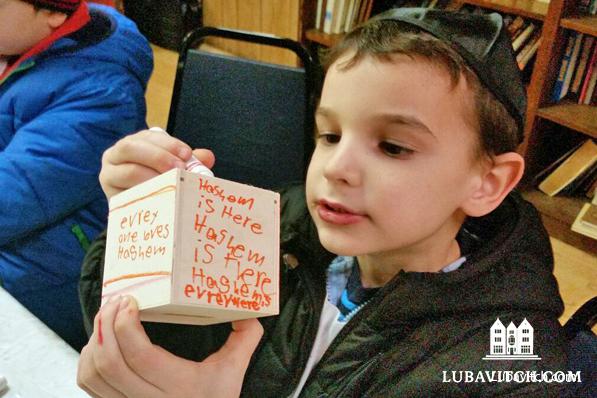

Hands-on activities get students excited about the weekly “Wednesday Hour”

Hands-on activities get students excited about the weekly “Wednesday Hour”

In the early 1970s, Steven Shenkman would walk from PS 253 in Brooklyn to a synagogue down the block. “It was only an hour a week,” he recalls, “but it made me realize how important it is to be a Jew.” Those lessons stuck with him and he eventually attended bar mitzvah training before his thirteenth birthday. But why didn’t he switch to a Jewish school? “Was it finances? Was no one motivated? I don’t know, but it wasn’t ever a discussion.”

Decades later, Steven’s twin children were proud Release Time attendees. Same hour, similar curriculum, but the experience was very different. “Unlike my parents, I brought my kids to the Jewish Hour and befriended the teachers. They would come to our house for the holidays. They lit the candles with us on Chanukah, told us stories, brought us matzah for Passover. And always, they were encouraging us to take it to the next level.”

After four years of friendship and gentle prodding, Steven enrolled his three children in a Jewish school. “There’s only so much you can learn in an hour,” the proud dad explains, “and I was worried they would forget what they had covered. Now they are happy and growing in yeshivah. It started with me and continued with my children. We have no regrets.”

“In recent years, the program has been greatly improved and enriched,” shares Rabbi Faivel Rimler. As a yeshivah student, Rabbi Rimler and his friends would gather kids for weekly study sessions. In 1957, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, tapped him to lead the organization. And four decades later, Rabbi Rimler is still leading it. “Contemporary instructors,” he says, “have a tremendous amount of savvy and they relate well to today’s youth. In the early years, most of our contact was with the students during that one hour. Now that we emphasize follow-up and a closer connection with the whole family, there has been tremendous success.”

In its eight decades, Released Time’s Jewish Hour has inspired 5,000 students to switch to Jewish schools. This past year, sixty Released Time kids have spent their first year in yeshivah studying Jewish lore and law alongside math and science.

For every child who makes the switch, there are dozens more whose primary Jewish education is the Wednesday hour. And instructors make sure it is a meaningful one.

Rabbi Yehoshua Shneur spent three years teaching kids from several Staten Island public schools. Age-appropriate prayers are followed by stories, crafts, and snacks. Before Passover, Shneur brought the children to eat outside the synagogue so that it would remain clean for the holiday. On Sukkot, the children munched on snacks inside a sukkah. Teachers visited each family during Chanukah to light the menorah together and share holiday treats. “More than book learning, it is these small experiences they have when they are young that stay with them,” Yehoshua believes. “Further down the road, they will remember those details, remember they’re Jewish.”

One of those kids with good memories is Steven Kogan, now an IT professional in Brooklyn.

“Released Time was my only sanity as a kid,” he says. “They brought us in to give us kosher snacks and food for thought. It was so different from school where the feeling was, ‘sit down and shut up.’ They taught me how to think.”

Today, Steven is married to a “nice Jewish girl” and is involved in his local community. “Am I very religious? Absolutely not. But I remember the stories, I connect back to what we learned, I teach others. I got an education there I couldn’t have gotten anywhere else.”

Steven is typical of many Released Time kids who come for the short sessions that are then imprinted on them for the long haul. “We try to reach each soul by igniting a spark,” says current director, Rabbi Zalman Zirkind. “Whether we want to believe it or not, reciting a blessing, hearing a story, singing a Jewish song is how the spark is ignited. And if a child wants more, we encourage him or her to take the next step.”

A P.S. group on a trip to Chabad Headquarters in Brooklyn

A P.S. group on a trip to Chabad Headquarters in Brooklyn

Be the first to write a comment.