Amid a national discourse about the transformation of America’s school system in the wake of the pandemic, Jewish day schools are enjoying an unexpected boost: Jewish families who previously relied on the public-school system are considering a day school for the first time, and many have made the switch.

Rebecca M.* began seventh grade this past September at a new public middle school in a suburb of Boston, Massachusetts. She completed sixth grade online, where, for months, she struggled to log on to constantly changing classes and keep up with school work via Google Classroom checklists. For her, the greatest difficulty was social distancing from her friends. While she joined in the fun TikTok videos about pandemic life, it wasn’t the same as hanging out in person or saying a proper goodbye before her family moved.

Even more confusing to the twelve-year-old adolescent was this year’s new routine: two days a week of in-person classes and the rest online. On the first day of in-person class, Rebecca was anxious. With her face hidden behind a mask and a six-foot distance between herself and her classmates, no one knew who she was. Her teachers, juggling their educational responsibilities along with a bevy of strict regulations, hadn’t been able to make sure Rebecca was feeling welcome in her new school. Then the school ended in-person classes and went fully online.

Elinor Ben-Yochai, 11, also spent the spring struggling to keep up with classes on Zoom at her New York City public school. While teachers checked in on occasion, Elinor was largely teaching herself, says her mom, Chaya Ben-Yochai, who was busy helping Elinor’s five- and nine-year-old siblings with their virtual classes. The five-year-old barely sat still for lessons, while the nine-year-old, who normally gets additional learning support in school, quickly fell behind.

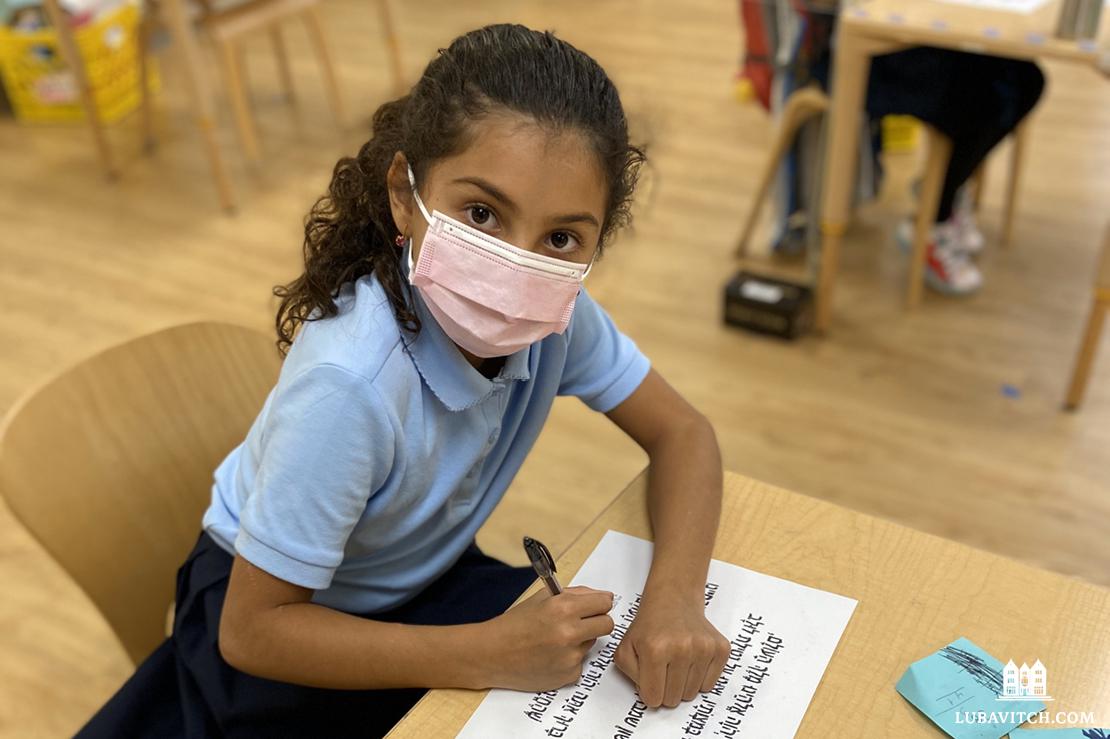

Like Rebecca, Elinor also switched schools, but she moved to a Jewish day school that opened with in-person learning. Her teachers carefully designed the classroom seating to ensure that she made new friends and stayed after class to help her catch up in Judaic subjects. Elinor loves going to school every day and, she says, she hopes she’ll never have to attend a virtual class again.

Across the nation, school options, and the support they provide, vary widely, and the differences between them may determine whether children sink or swim this school year.

COVID’s Impact on Schooling

When the pandemic first hit America’s shores early last March, it created chaos in the world of education. Schools across the country were forced to shut their doors overnight, and administrators and parents scrambled to provide students with some semblance of a learning routine. What emerged was a great divide between the way public and private schools responded. Jewish day schools were the very first schools in the nation to shut down. Yet within days, SAR Academy and Westchester Day School in New York had their students learning live via online platforms. Public schools, by contrast, took weeks and even months to move online last year. Some never got there at all.

“Jewish day schools have been showcased at their best during this crisis,” says Paul Bernstein, CEO of Prizmah Center for Jewish Day Schools. “Across the board, [Jewish day schools] pivoted incredibly quickly and incredibly well to virtual forms of teaching.” And Jewish families took notice.

Lubavitcher Yeshiva Academy (LYA), a K-8 day school in Longmeadow, Massachusetts, closed its doors on Friday, March 13, 2020, as soon as the state governor gave the order.

Rabbi Noach Kosofsky is the principal and director of LYA. “In Judaism, saving lives is of paramount importance. We understand that the governor closed all schools statewide to stop the spread. We were committed to maintaining safety for the health of the community.” At the time, schools were told that they would be closed for two weeks. Kosofsky wasn’t willing to wait that long to restart classes.

The children needed to learn, and by Monday morning, the school had secured an online learning platform, and students logged in from their homes.

“It wasn’t perfect right out the gate. I was concerned that if we didn’t ask the children to show up to classes, they wouldn’t take online learning seriously, or they would be out of a routine. We also wanted to check in on everyone to keep our students’ spirits up.”

Like many Jewish day schools across the country, LYA invested early in training teachers in distance-learning techniques. Accessibility was also immediately addressed. With help from local donors and Jewish Federations that stepped up to the plate, a host of Jewish day schools distributed tablets or computers to students who needed them, and helped families troubleshoot the new technology.

Kosofsky says that the months of distance-learning raised many unforeseen challenges. Some teachers struggled with the transition to instruction in a completely digital format; students had a hard time concentrating, and parents were overwhelmed trying to juggle it all. As many families around the world experienced first-hand, virtual school is, by nature, limited in its ability to deliver a well-rounded educational experience to children. In Education Week, a researcher concluded that overall, online classes are not as effective as in-person classes, and that students who struggle with in-person classes are even more likely to struggle online.

As the academic year wound down, Jewish day schools began taking stock of the learning experience they were providing their students. Some began to worry about the coming school year. Would parents stick with them in a Covid-19 world?

Anna Ashurov is president of the board of trustees at Mazel Day School in South Brooklyn. “We were concerned that there would be a high attrition rate to public schools. There was always a risk that parents would opt-in for a free, all-virtual public school option.” She explains that safety, positive influence, and close-knit community are some of the main reasons why Mazel parents choose the private school option. “Taking the negative connotation of in-person public school experience out of the picture, families might have found it acceptable to enroll their children in tuition-free virtual schooling, especially after the devastating economic impact that the pandemic had on communities across the U.S.”

Putting Children, and Safety, First

As states and districts began considering how to reopen schools this past fall, the discussion reflected a familiar tension: the need for safety had to be balanced with the needs of children. Health and education experts say that the data is overwhelmingly clear on the importance of in-person schooling. According to the CDC, “extended school closure is harmful to children… [leading] to severe learning loss.”

Pediatricians and educators say it is critical to weigh the risks of the virus against the very serious social, academic and mental health risks of extended online learning. The American Academy of Pediatrics, American Federation of Teachers, National Education Association, and School Superintendents Association released a joint statement earlier this year urging schools to safely resume in-person learning, asserting that “children learn best when physically present in the classroom.”

Parents are on board. More than half of American parents with children from kindergarten to twelfth grade strongly favor a return to full-time, in-person schooling.

In late spring, Chani Okonov, the Head of School at Mazel Day School, put together a taskforce of educational experts and parents—many of whom were physicians—to determine the best and safest way to open the school in the fall. “At that point, some schools in Europe were opening,” she says, “so we carefully followed the available data and committed to what we determined to be the best guidelines for mitigating risk.”

Working with her team, Okonov reconfigured every classroom to provide socially distanced desks for the school’s 330 students, installed polycarbonate barriers where needed, and medical-grade air purifiers. Mazel also instituted universal mask-wearing, a “zero tolerance” sick policy, daily health screenings, and nixed all group gatherings. Okonov was clear that there would have to be a contingency plan for every possible scenario—from a hybrid model, where some students could choose to learn online, to an easy transition to a fully online program, should it become necessary.

At LYA, Kosofsky invested heavily in precautions that surpass CDC requirements: water-bottle filling stations have been installed in place of water fountains, ionizers that can kill virus molecules added to the HVAC units, and gazebos were built for outdoor learning. LYA students sit at desks with plexiglass dividers; parents are not allowed on campus, and mask-wearing and social distancing are strictly enforced.

Jewish day school classes tend to be smaller, with greater ability to monitor potential outbreaks. Without the encumbrance of a red-tape-laden approval process, independent schools can quickly and easily set their own guidelines and institute rigorous protocols for cleanliness, testing, and enforcement. Many schools are offering a hybrid option, where students can opt to learn online (as a personal preference, or if they are in quarantine).

The individualized approach works. According to the COVID-19 School Response Dashboard, a website that analyzes data culled from many national school associations, private schools are seeing much lower infection rates than their public counterparts.

In Burlington, Vermont, Draizy Junik of Tamim Academy faced a different challenge. She and her husband had planned the launch of their new Jewish day school—the first ever in Vermont—for the fall of 2020. Junik consulted with experts to ensure that the new school could open its doors. Some lessons were moved outdoors, and a hospital-grade ventilation system was installed in the classroom. A small student body helps—there is only one mixed K-1 class, with thirteen students.

“It was incredibly important for the school that everyone involved felt comfortable with the safety measures in place,” Junik says. “We let the science guide our decision-making, and I personally followed up on every concern that a teacher or parent raised. We were going to do what we needed to do to open for our families.”

That commitment to community is echoed by Jewish day schools across the nation, a fact that is noticed and appreciated by families. Sarah Winston lives about a forty-minute drive from Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Her son, Jack, is a precocious two-year-old who needs extra help in language development and socialization. During the stay-at-home orders in the spring, he showed early signs of regression.

“Jack is a hands-on learner and really benefits from a school environment. We had hoped to send him to a local Conservative Jewish preschool this fall, but they decided not to open. I gave LYA a call and was so thrilled that they had the right temperament and organization needed to open. It is a big responsibility, and you need that persistence, because, as a community, we really need them.”

Winston gave birth to a baby in April, and her husband cares for his eighty-nine-year-old mother, who lives down the street. “With a newborn at home and a high-risk relative, we need to weigh every exposure carefully,” she says. LYA’s strong safety plan made her feel comfortable enough to send Jack, and also willing to make the forty-minute drive to Longmeadow every day.

A few months in, Jack is thriving. “It has made such a huge difference. He’s coming home singing, ‘Torah, Torah!’ He’s so enthused that he has friends, and his language has jumped by leaps and bounds.”

A Silver Lining in the Storm

From a speedy uptake of successful online learning in the spring, to safe reopening of in-person or hybrid instruction this fall, Jewish day schools have far exceeded public schools in the quality of and access to education they have managed to offer since the start of the pandemic. The contrast has attracted interest from Jewish families who had previously not considered a Jewish day school for their child.

Jewish day schools across the country are reporting increases in enrollment. Recruitment remains strong well into the school year. “As soon as we announced late in the summer that we would be opening five days a week in person, we were inundated with calls from families interested in enrolling for the new school year,” shared Okonov. “Our fears of attrition were completely reversed, as more families than we could accommodate reached out.”

To date, about twenty children—most of whom are in the school’s exact target demographic—moved from public school to join Mazel Day School. “Many of these are families who have friends in our school. They have those ties and interest in the community, but, for different reasons, have chosen public schools in the past. Once they have come through our doors, they have all the community support in place to stay. They are excited about the opportunity to now give their children a Jewish education”.

Ashurov is more emphatic about parents’ disenchantment with the public-school system.

“Public schools in New York City have been a big disappointment throughout this journey. There is a lack of clarity and certainty in what the year will look like for most New York City students. Our state and city had eight to nine months to prepare for reopening in the fall, but not surprisingly, they still don’t have it figured out. At Mazel, my children were immediately part of a comprehensive program with full-day live instructions starting in March. This year, our school is offering a much better product than public schools,” she says.

Last year, Jennifer Liberman sent her ten-year-old son to Success Academy, the largest charter school network in New York City. When she learned that they would not be reopening in person this year, she enrolled him in Mazel Day School. “We saw that with remote learning, he was not putting in his best effort and the quality was lacking,” says Liberman. The fact that her son was entering middle school also factored into the decision to make the big switch. “At this age, it is so important who he hangs out with. We wanted him to get to know his culture and his heritage.”

“The silver lining in all of this is that the new families that joined our school this year are truly enjoying this new experience and will be great advocates for Jewish day schools, now that they’ve experienced both products first hand,” Ashurov says.

Mazel Day School did see a few families leave, mostly for reasons related to the Covid-inspired urban exodus from New York City. Still, attrition to the suburbs is an ongoing trend that the school anticipates. This year’s rate was about the same as a typical year, and the influx of new families has more than made up the discrepancy.

The outward-bound trend has been a boon to Jewish day schools outside of the Tri-State area. Vermont has been one of the most popular places to move to for families fleeing hot zones. That has benefited the brand-new Tamim Academy in Burlington, which saw a last-minute enrollment increase. Junik, the director, says the school is made up of one-third graduates from their preschool, one-third local families and one-third families who have recently moved to town.

Batsheva Nagel never really considered moving out of the Pomona, New York, area where she has raised her four children, but when the perfect property came on the market during the lockdown, she and her husband made a spontaneous decision to move. “In New York, my children were used to a more traditional, yeshivah-style education of sitting behind a desk for eight hours a day,” says Nagel. That rigidity worsened with the switch to online schooling from home. “It is really hard to develop a relationship with children over the computer. My kids are sensory and high energy. It’s hard enough for them to sit face-to-face in a classroom, let alone on Zoom.”

The move to a smaller school that prides itself on hands-on experiences got her children back to learning. Nagel is pleased with the quality of education her children are receiving at Tamim Academy.

For some schools, the enrollment increase has completely changed the playing field. The Academy of the Arts in Redondo Beach, California, is located in one of the country’s highest-rated school districts. Families move to the area specifically to send their children to the excellent local public schools. When Rabbi Yossi Mintz established the Academy three years ago, he knew it would be an uphill climb.

“We had to compete with excellent, well-resourced public schools. We knew we weren’t going to be drawing in families just by being a Jewish school. We needed to not only match, but outdo other schools in the level of education we offered,” the rabbi explains. To do that, the school enlisted the talents of Dr. Debra Bogle, a former USC professor of education who has written nationally recognized curriculums. With the help of a highly successful preschool as a funnel for Jewish families, the school slowly built up its student body to thirty-three children in grades K-2 last year. This year, they added third and fourth grade, as enrollment more than doubled to eighty students and counting.

“We have a long waiting list and are trying to figure out how to safely accommodate the huge spike in interest,” Mintz says.

Much of the interest stems from the closure of local schools with no clear date of a return to in-person classes. “Even in such a strong district, parents are not happy. The online version is just not working for kids.”

According to Mintz, the situation has changed the equation for families who could afford to send their children to day schools, but “weren’t committed to the value proposition.”

For those already enrolled in Jewish day schools before the pandemic, the experience has been affirming.

“Having online school was the ultimate open-door policy for our parents,” says Okonov. I think it reassured them about the level of academics we offer and showed anyone who may have had second thoughts that their children were receiving a balanced education. But more than anything, the feedback from parents has been about seeing their children participate in a community and gaining a sense of belonging.”

Building on the Momentum

For Kosofsky, no matter what happens this year, the efforts to open have already paid off. “Every day, when I walk into school, I see happy kids. It is the most beautiful thing.” He describes the lunch room, where two students are sitting six-feet apart at an eight-foot table and are just excited to be there with their friends. “Three months into the school year and it is still a novelty for them. They are grateful to be in school.”

The appreciation is perhaps even greater among the many first-time Jewish day school enrollees. But is it enough to make them want to stay?

Chaya Ben-Yochai is convinced that it is. Her daughter’s successful experience at Mazel Day School has solidified her commitment to providing a Jewish education to her children—despite the costs. “My husband and I decided that it is a sacrifice we have to make for our kids. We want them to have a strong Jewish background, and we don’t have the knowledge to give that over to our children in the way a real Jewish education can.” While her eldest, Elinor, is thriving at Mazel Day School, her younger two children could not be enrolled due to space constraints. Both children are struggling with virtual school this year, and Ben-Yochai is actively applying to other Jewish day schools in the hopes of making the switch.

Bernstein, who directs an organization that works with Jewish day schools across the country, believes the pandemic has shed new light on the added value of a Jewish education. “Parents are realizing how Jewish day schools view their responsibility towards educating and caring for the whole child. It is a perspective that perhaps hasn’t been appreciated for its critical value until now.”

Mintz doesn’t know what re-enrollment numbers will look like next year, but he is staying optimistic. “Right now, our goal is to provide really personalized attention to each child for the most positive learning experience possible. If we do our job right, it is going to be hard for parents to leave.

“We have eight months to prove our worth. We are just getting started.”

*Name changed for privacy.

This article appeared in the Lubavitch International Winter 2021 Magazine. To subscribe and gain access to previous magazines – click here.

Be the first to write a comment.