(lubavitch.com) Natan Sharansky, Chairman of the Jewish Agency since last June, announced a shift in the organization’s mission that has sparked wide discussion.

The famous Soviet dissident who made headlines for standing up to communist authorities during the 1980s, attributes his fearless perseverance to a discovery he made as a young man: the vitality of his Jewish identity.

Sharansky insists that despite postmodern attitudes scornful of particular loyalties, especially those tied to religion and family, today’s challenges to Israel and the Jewish people are best overcome through the active involvement of Jews who are educated about their heritage and passionate about Jewish life.

The diminutive figure who survived numerous, months-long hunger strikes during his near decade of incarceration, and was prepared to fight to death for his values and deeply held principles, is hoping for more than token allegiances to Jewish life. The author, most recently of The Case for Democracy and Defending Identity, Sharansky is guiding the Agency to develop a program that will foster a meaningful connectedness to Jewish history among young Jews, and translate into a tangible commitment to the future of the Jewish people.

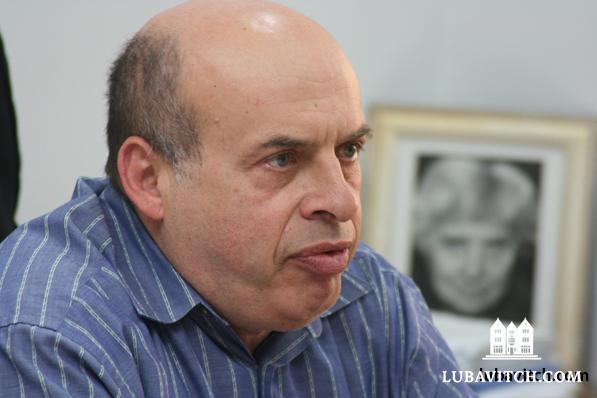

Recently, Mr. Sharansky met with Baila Olidort, editor of Lubavitch News Service in his office at the Jewish Agency’s headquarters in Jerusalem, where he talked about his vision, his respect for Chabad’s model of outreach, and the moral ambiguities he discovered in freedom.

Q: As Chairman of the Jewish Agency, you are going to refocus the organization’s agenda and make building Jewish education and Jewish identity a priority. Why the change?

A: It’s not that the aims of the Jewish agency have changed. The JA was created in order to mobilize Jewish people around the idea of the Jewish state, and to bring Jews who want and who need to be saved, to Israel. They brought 3.2 million Jews over the years. Billions of dollars were raised and hundreds of settlements and towns were built with the help of world Jewry.

But those operations of saving Jews whether from the Iron Curtain or Arab countries or from Ethopia are now behind us. Today aliyah is aliyah of choice and those who do it, do it because they have a strong commitment to the Jewish people, a commitment to live in a Jewish state.

In that case, what are the challenges as you perceive them today?

Today our challenge is whether we can stick to our identity when we have the freedom to choose our identity.

It’s clear from your books that you were prepared to die for your principles.

It wasn’t a decision about suicide, it was a decision about was important for me in my life.

In my life in the Soviet Union I had no basic freedoms, but I had no inner sense to fight, because to do that you have to feel that there’s something more important than physical survival. And in the Soviet Union it was all about physical survival.

It was only when we discovered our identity and began to connect with it, that we found that there is something more important than physical survival.

That’s why I wouldn’t compromise with them—I wouldn’t give away my inner freedom for physical survival.

Is the Agency’s focus primarily on Jews living in the Diaspora?

Not only for Diaspora Jews. We need to strengthen Jewish identity everywhere. People here sometimes underestimate how important it is for Israel.

The JA is going to be much more involved strengthening Jewish identity in the state of Israel.

Jews of Israel sometimes feel themselves more as Israelis than Jews. They are losing their historical or cultural connection with their Jewish roots.

So what are some of the ways the agency will work to strengthen Jewish identity?

The Jewish Agency is a main channel of communication between the Israeli government and Jewish communities around the world. So when Jews from Israel meet other Jewish communities abroad, and spend some quality time inside [those communities], or have mutual projects with them, it helps to strengthen their Jewish identity.

As American Jewry discovered, it’s important to strengthen forms of informal Jewish education, especially for people who don’t get a formal Jewish education—whether it is through summer camps or different seminaries. We are doing it, but we have to do it more.

What you are proposing resonates with the work of Chabad-Lubavitch. Do you see the Jewish Agency cooperating with Chabad on some of these projects?

We already have this cooperation. In the FSU there are many places where our representatives sit in the centers of Chabad, and on the contrary where Chabad is using our facilities, and I am very much in favor of this.

On campuses as well, we are broadening on our activities there, and Chabad is doing the same and we welcome it. I meet more and more Chabad rabbis on the campuses and we will have more of our shlichim on campuses.

We can learn a lot from the determination, stubbornness and persistence of Chabad shlichim.

When [some] representatives . . . came to me and asked me how it is that I gave all of Russian Jewry under the control of Chabad, I said, what do you mean “we gave?”

“Well, it’s all their shlichim and not ours. It’s not fair,” they said.

I promised them that the moment they have a person who is ready to go for all their lives—like to exile—to Omsk or Perm or Kamtchatka or Sakhalin, as Chabad shlichim do, not one month, not one year, but to spend all their lives there—and look what happens: a Chabad shliach comes with wife and one child, and there are 10 Jews and he spends 10 years there. Now he has four children, and there are 150 Jews who appeared from nowhere, and he is building a community and he spends another 10 years and community is becoming even bigger—

“If you have such people,” I told them, “I promise we’ll help them go to Sakhalin or Kamchatka.”

Jewish universal values are widely embraced everywhere. What are some of the specific Jewish values that you want to promote in your work in the JA?

Personally, I’m glad that my daughters have a traditional Jewish life. My wife keeps more of the mitzvot than I keep and my daughters even more than my generation.

As far as the Jewish Agency, we do want more and more people to be connected in different ways to their heritage, to the values of Judaism and to wish that their children will be no less committed Jews than their fathers were. But we here are not religious –we have representatives of all the streams and we are not going to impose in any way.

Still, I do believe that it is absolutely a wrong statement that you have to choose whether to be a person of universal values or of Jewish values. It is as false today as it was before. There’s a deep connection between the two—if I have the strength to fight for human rights it’s only because I discovered my Jewishness.

Towards the end of your book Fear No Evil , which you wrote shortly after you gained your freedom, you expressed some sadness about leaving your life in Russia in prison. You talked about the absolute certainty between good and bad, and you wondered whether once in the free world, you will know “how to enjoy the vivid colors of freedom without losing the existential depth” that you felt in prison.

I have to say that now [so many years later], I’m surprised how right I was then—to see this as a major challenge to my life. I was in this place where there was such clarity between good and evil, friends and enemies. And it’s practically impossible to reach this level of moral and practical clarity in daily life.

I spent nine years in prison, but I also spent nine years in government. I was in four different governments and I resigned twice. I was in four different prisons, I never “resigned”—so there’s some deep dissatisfaction from our daily life [about the fact] that you really cannot get this stage of clarity—you have to go through all sorts of compromises.

You’ve gone back to visit Russia and the prisons where you spent so many years of your life. What was it like?

The first time I went was 10 years after my release. And it was such an elevating experience. To think that this was the place where the leaders of the KGB—the most powerful organization in the world—told me that this was the end of Jewish movement, that every Jew is afraid to mention our names, and instead, 20 years later, there is no KGB, no Soviet Union, and the world is a more secure place.

Each time when I go back I have this feeling that this is the place where we tested and proved our power as a people. So it is important to draw the right conclusions about what can be done today.

As a Soviet prisoner, you dreamed about Israel, about one day living here. You’ve been living here now 24 years. How does the reality meet your expectations?

I dreamed that Israel is a paradise. And 24 years later I feel it’s the best place for a Jew to live but it needs a lot of tikkun. A lot needs to be corrected. Morally, it is much more difficult to live in paradise than in hell, because in hell you knew exactly what your role is.

What was your greatest disappointment?

When we were struggling, all our friends had the feeling that we are one people, and it was so clear that we are one people. But when I came, I discovered that there’s no limit to the divisions among us—and to this day this is very disappointing and frustrating.

Still, we see that at critical moments, these walls fall apart and we become one people again. So this is our biggest challenge: to make these walls come down.

What is your greatest concern regarding Israel?

Today we have a big problem of advocacy for Israel, of defending the very idea of a Jewish state today. And again, people who are ready to fight against new hostile anti-Semitism are people who have a commitment, connection and strong feeling of family—people who want to make sure that their children will grow as Jews and will continue being part of the family.

So whatever challenges we are facing, we will come to the same driver to solve the challenges: to strengthen our Jewish identity.

Be the first to write a comment.