The past few months seem to have passed by differently. Our focus has been drawn to the Land of Israel. We have counted the number of days that the hostages have been in captivity, the weeks and then months since the deep traumas of October 7. We find ourselves looking back, even as we anticipate, and obsess over, what the future holds. Sometimes it feels as though eons have ached by, but, then again, the wounds feel as fresh as yesterday.

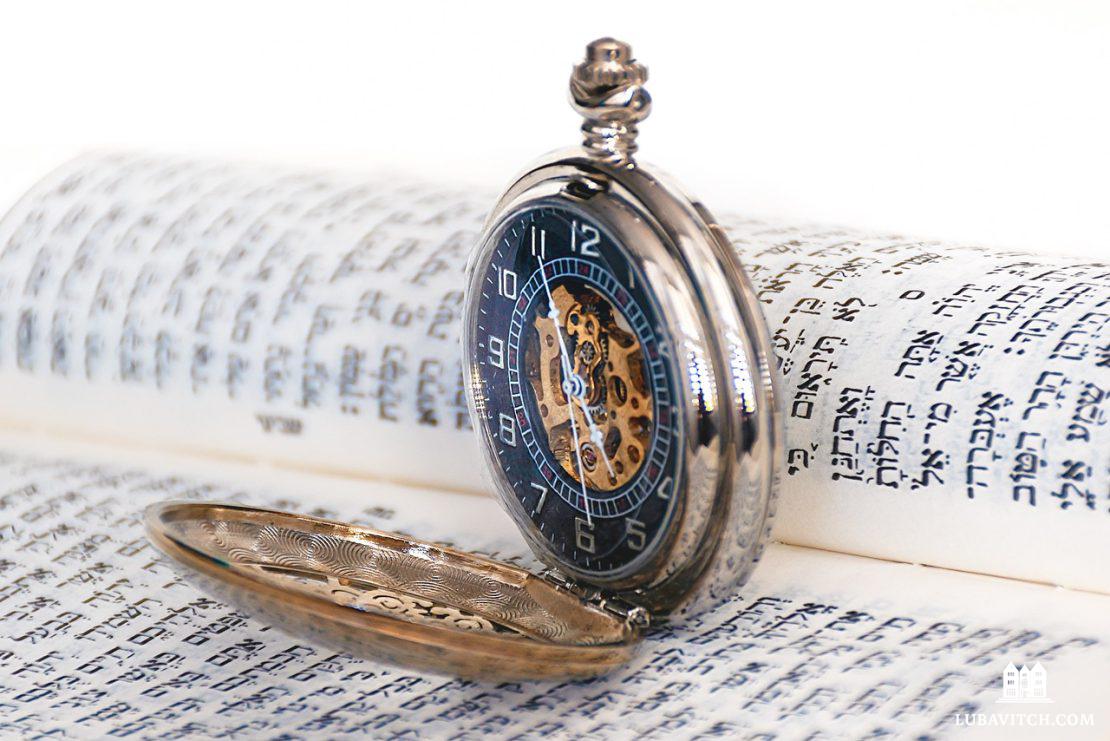

Counting days is an age-old Jewish practice, a way to imbue time with meaning, purpose, and sanctity. We count the six days of the week until Shabbat, the seven years of the agricultural Shemita cycle, the fifty years until the Yovel Jubilee. The definitive ritual of Jewish counting, however, is the Counting of the Omer. The forty-nine-day count begins on the second day of Passover—when the Torah commands us to bring a special barley offering known as the Omer—and culminates with the festival of Shavuot, the fiftieth day—which also commemorates the giving of the Torah.

The practice of counting the Omer—known as Sefirat HaOmer—continues to this day, even though no such offerings may be brought until the Holy Temple is rebuilt in Jerusalem. This year, from Tuesday, April 23 until Monday, June 10, we recite a special prayer each evening, noting the days and weeks “of the Omer.”

Sefirat HaOmer contains endless depths, as successive generations have added new layers of meaning. In Sefirat HaOmer, we look backward—recalling the lost Temple service and praying for its restoration—and forward to the multifaceted festival of Shavuot. We look within, using the time for personal introspection and self-improvement, as well as without, fostering ties of Jewish unity and mutual respect. It is also a time of mourning, as we commemorate the losses and tragedies that befell the Jewish people, and therefore also of healing. It is a time of change, transformation, of prayer, and of hope.

Several insights have been collected here from sources both ancient and contemporary, on the meaning of the Sefirah count and the lessons to be learned from this phase of the Jewish calendar.

Why Count?

What can counting days accomplish? The days are there whether you take note of them or not; they do not pass by any faster or slower when you count them.

In the case of the Omer, counting the days leading up to the holiday of Shavuot becomes a significant act because it is a mitzvah. The divine command calls the count into ontological existence. The forty-nine days become imbued with importance, and, when the Jew counts them properly, these days are transformed into sacred time.

In this, the Omer period is a highly apt preparation for the giving of the Torah: Just as the commandment to count creates the count, so it is said that the entire world was created for the Torah, and on condition that we receive the Torah. When we fulfill the Torah and its commandments, we help the world fulfill its purpose, by making the world a divine place.

Sefirat HaOmer is unusual in another way. There are many other commandments that are time-bound, and can only be performed at specific times of the day or year –– sounding the shofar, reciting the Shema, eating matzah, and so on. But in all these cases, time provides context for the ritual; the actual substance of the ritual—a ram’s horn, a set of words and intention, unleavened bread—is another thing. But Sefirat HaOmer is different in that the very substance of the ritual is time itself. Thus it affects the very fabric of reality, which is composed of space and time, and gives us the power to act within reality, drawing down the divine through the performance of other mitzvahs.

––The Rebbe, Likkutei Sichot, vol. 38

Measuring the Minutes to Freedom

The Jewish people were redeemed from Egypt so that they might receive the Torah on Mount Sinai and fulfill it. For this reason, we are commanded to count from the second day of Passover until the day the Torah was given, to show in our spirits our great desire for that gift. Our hearts have longed for it, like a slave who measures the minutes until he will go free. For counting demonstrates that his entire salvation, and his entire desire, is to reach that time.

Therefore, we count upward and not down, since at the beginning of the count, we do not wish to bring discouragement by mentioning the many days that remain [and instead only note the days that have passed]. We do not change this formula, even as we approach Shavuot.

––Sefer HaChinuch, 306

Counting from Disbelief

Imagine that a person was being held in prison, and one of the king’s servants came to him with a message, telling him: “On such-and-such day, the king will free you from the prison, and then, fifty days later, he will give you his daughter as a bride.”

Said the prisoner: “If only he would just free me, and no more!”

But then, when the king freed him, he said, “Since his words about the king freeing me have been fulfilled, surely the second part of the message will also be fulfilled.”

And he began counting fifty days . . .

So, too, when Moses told Israel that they would be redeemed and receive the Torah, they were so weary from their labors that they did not listen to him. They said: “Even that He will take us out of Egypt, from slavery, we cannot believe.”

So it was, until they went out of Egypt. Then Israel began to count the days until He would give them the Torah.

––R. Yosef b. Yitzchak of Orleans, Bechor Shor

Destination Unknown

Today, the counting of the Omer recalls the Jewish people counting the days from the Exodus to the giving of the Torah at Sinai. But, as the Sefer HaChinuch asks, if the Jews were so eagerly awaiting Sinai, shouldn’t they have been counting down? Why does the Omer count go up, from one to forty-nine?

When G-d told Abraham to leave his homeland, He did not tell him the destination would be the Land of Israel; when the Jews were told they would build a permanent Temple in Israel, they did not know it would be in Jerusalem. We do not know when G-d will send Moshiach, and yet we wait.

Perhaps, suggests Rabbi Y.B. Soloveitchik, the same thing happened after the Exodus. G-d told the Jews that they would receive the Torah, but did not say when. And so they—and we today—continue to count upwards; uncertain, but unshakeable.

––R. Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, Pninei HaRav

Standing in Solidarity

During the time between Passover and Shavuot, “the world is in distress,” as farmers prepare for, and fret over, the annual grain and fruit harvest.

This is one of the reasons G-d commanded us to count these days. By reminding ourselves to count each day, we will remember the pain of the world, and we will remember to return to G-d with a complete heart, and to beseech Him him to have mercy on the land.

––R. David Avudraham, cited in Otzar HaTefillos

Extra Protection

The period from Passover to Shavuot must be guarded. During the harvest, the Midrash says, we are vulnerable to “evil winds and bad dew” and other forces beyond our control.

Since one needs extra spiritual protection during this time, G-d commanded us to count and to anticipate, from day to day, towards the giving of our Torah. This way, we merit being saved, because we are observing a mitzvah each day, and “one who observes a mitzvah will know no evil.”

––R. Mordechai Yosef of Izhbitz, Mei HaShiloach

Unpacking the Experience

The mystics teach that on the night of the Exodus, the divine revelation was so great that the Jewish people could not fully absorb it. Therefore, G-d gave us the commandment of Sefirat HaOmer, that is to count and measure out, for fifty days, until the holiday of Shavuot, allowing us to arrive at an appreciation of the revelation.

Imagine a father walking with his son, and then finding a treasure trove of gemstones and pearls. The son is unable to appreciate the great value of these precious things, but the father commands him to pick up as much as he can carry.

“How much is this worth?” asks the son.

“Now is not the time to occupy yourself with this, and to tell you the value of this treasure,” answers the father. “Just be strong, my son, and take what you can, with haste and with fortitude. When you arrive home, then you can count and measure what you have gathered, and I will tell you its worth.”

So does G-d shine a light that is beyond our capacity to absorb on the first night of Passover. Then, through the days of the Counting, we contemplate and slowly come to appreciate it, until on Shavuot we have a full understanding of its true value.

––R. Mordechai Yosef of Izhbitz, Mei HaShiloach

Students or Soldiers?

Many explanations have been offered for the various mourning practices observed during the Omer period. The trail of destruction wrought by the First Crusade of 1096 in the Jewish communities of the Rhineland, and the tragic passing of twenty-four thousand students of the great sage Rabbi Akiva were concentrated during this time of year. The Talmud (Yevamot 62b) ascribes a spiritual cause to this latter plague: It was because these students, despite their association with the saintly Rabbi Akiva, “did not accord respect to each other.”

In more recent years, certain scholars have linked these events to Rabbi Akiva’s known support of the great Jewish revolt against the Romans, led by Bar Kochba, in the second century C.E. According to this view, Rabbi Akiva’s students may have participated directly in this war, by taking up arms against the legions of Rome.

The sources for this conjecture remain somewhat dubious, and it finds little support in the historical record or in traditional sources. However, some have used it to advance a lesson that is perhaps even more relevant today than ever before.

The lack of respect among the students of Rabbi Akiva, which the Talmud alludes to, may refer to an ideological split among the Torah scholars of that period: While some believed in the necessity of fighting the Romans physically, others felt that a more spiritual kind of resistance was in order, i.e., that their primary task was to continue studying and teaching Torah. Each camp, convinced it had made the correct decision, believed itself morally superior to the other, and so the students began to demean each other. It was this senseless hatred that was their true downfall.

––Adapted from R. Eliezer Melamed, Pninei Halachah

A Circle or a Line?

What if someone forgets to count one of the forty-nine days of the Omer? According to the early medieval sage Hai Gaon, they may simply continue to count the remaining days. But a contemporaneous work, known as the Halachot Gedolot, disagrees: the person cannot continue counting and has forfeited the chance to fulfill the command.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has suggested that these two opinions reflect Judaism’s two conceptions of time itself.

The first, which Judaism broadly shares with the belief-systems that preceded monotheism, is “cyclical time.” Each week, we return to Shabbat; we follow the orbit of the moon to set our calendar; our annual festivals are tied to the agricultural cycle. The days and years repeat themselves as the universe is continually renewed, but they do not cohere or connect with each other into something larger, and ultimately, the world remains the same. This year’s Pesach is the same festival we celebrated last year, and this Shavuot, we are set once again to receive the same Torah that came down at Sinai. A person takes each day—with its challenges and its tasks—as it comes, on its own terms, and leaves the rest to G-d. In this view, represented by the opinion of Hai Gaon, the loss of one days’ count has no bearing on those that follow.

Then there is one of Judaism’s great innovations, which Sacks calls “teleological time,” or “covenantal time.” In this conception, time has a direction and a linearity, a starting point and destination, in which “each moment has a meaning, which can only be grasped if we understand where we have come from and where we are going to.” Thus, in the view represented by the Halachot Gedolot, each day of the Omer is another vital aspect of a larger period of time. In this view, time receives a purpose—and so do we. We became historical actors, capable of changing ourselves, transforming the societies around us, and bringing the divine message to the world.

–– Adapted from Covenant and Conversation, Maggid Books, 2009.

Every Man for Himself

In general, any mitzvah that involves reciting something—Kiddush on Shabbat, Havdalah afterwards, reading the Torah, and so on—can also be fulfilled by listening to someone else recite the relevant words. Not so Sefirat HaOmer; according to some opinions, like R. Mordechai Yoffe, author of the Levush, every man and woman must verbally count on their own. As the Torah says: “And you shall count for yourselves…” (Lev. 23:15).

Counting the Omer is part of a process of spiritual elevation and self-refinement, as we prepare ourselves to receive the Torah. If counting is part of a process of purification then, like immersing in a mikveh, one cannot rely on others to perform this spiritual work for them—each person must purify him or herself.

––R. Yitzchak Mirsky, Hegyonei Halacha

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of Lubavitch International, to subscribe to the magazine, click here.

Daniel

🇮🇱