Marnie Perlstein, an advocate against antisemitism in Sydney, Australia, calls herself an “accidental influencer.” When protestors burned an Israeli flag on the steps of the Sydney Opera House two days after the October 7 Hamas attacks, Perlstein turned her Instagram account—previously reserved for friends and family—into a channel for her rage. She has meticulously documented the surge in Australian antisemitism, called for the hostages’ release, and cursed the Australian government for its apathy. Within a few months her follower count climbed to the tens of thousands.

But on September 26th of last year Perlstein asked her followers to take a brief break from their indignation. It was the fiftieth anniversary of Chabad’s global candle-lighting campaign, and the Shabbat before Rosh Hashanah. Perlstein invited her followers to join people around the world who were lighting Shabbat candles. “At this point I’m looking for anything that will make the world a better place and spread light rather than darkness, and love rather than hate,” she wrote.

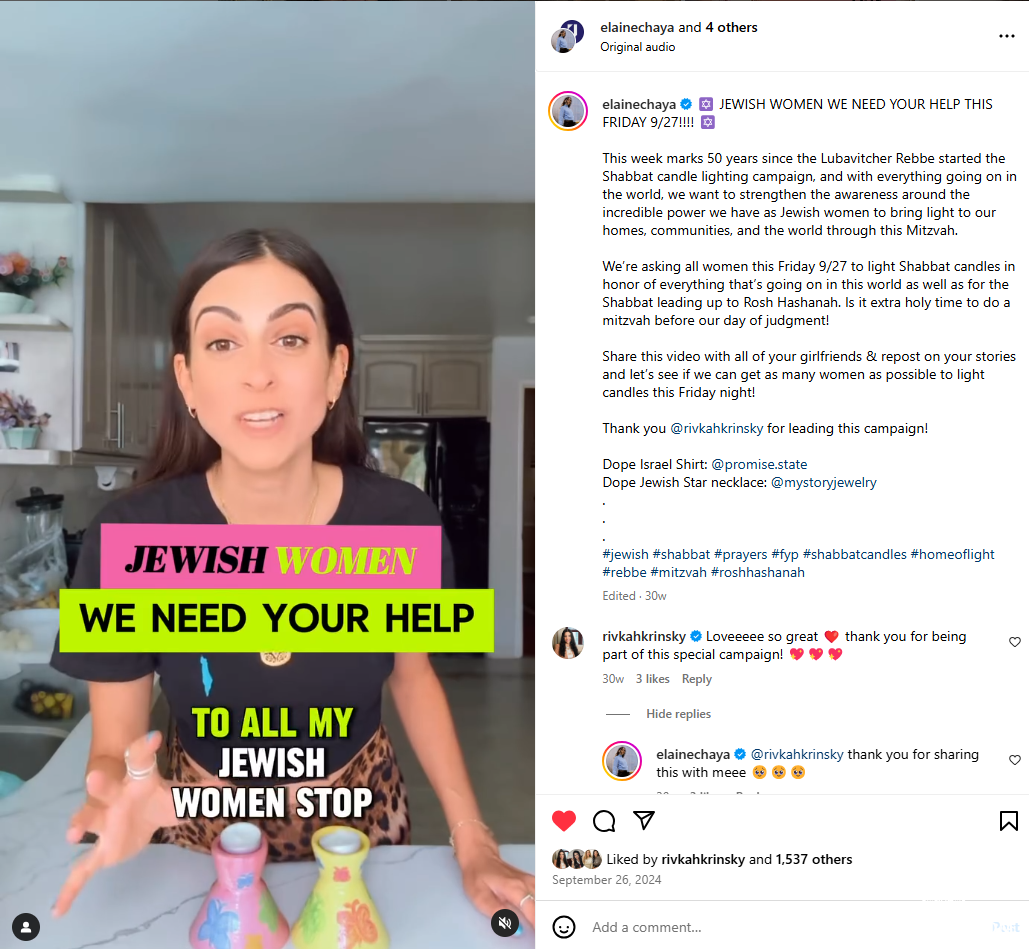

The same day Elaine Chaya, a fashion blogger and influencer based in Los Angeles, appeared in an Instagram reel standing at her kitchen counter brandishing porcelain candlesticks painted pink and yellow with butterflies. “Stop your scroll,” she told her Jewish followers; “we need your help.” She explained the Rebbe’s candle-lighting campaign, and then called her followers to action: “Married, single, religious, not religious,” she said, “with our light, we can make a difference.”

One of Elaine Chaya’s followers, a woman I’ll call Sandy, saw the reel and hesitated. Living alone in Los Angeles, Sandy felt the Hamas attacks and their reverberations keenly. “I’m scared to be Jewish,” she said. “I’m worried that I have a mezuzah on my door. Fortunately it’s covered by the screen door.” Sandy also identifies as an atheist, with choice words for any deity who could allow all the suffering she’s witnessed. She wasn’t interested in a religious ritual.

Still, following influencers like Elaine Chaya who proudly defended Israel gave Sandy a feeling of community. And the idea of doing something at the same time with a lot of other Jews appealed to her. She recalled how, as a young woman, she had driven past Jewish homes on Olympic Boulevard on Friday evenings and looked through their large, illuminated windows at tables covered in white linen and crystal in honor of Shabbat, thinking she might one day have her own such table. “This was kind of a throwback to that time,” she said, “to hope.”

Armed with Light

In September of 1974, a year after the Yom Kippur War devastated Israeli society and a month after President Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace, the Rebbe introduced a new mitzvah-campaign. Jewish women and girls should kindle Shabbat and holiday candles to bring light into a world that was spinning into darkness and chaos, the Rebbe said—even girls as young as three should perform the mitzvah. “The Rebbe felt the children would bring more light,” said Esther Sternberg, who has directed Chabad’s Shabbat candle-lighting campaign for the past fifty years. “They will do the mitzvah when they’re young. Then hopefully they’ll keep doing it, and it will keep them anchored to Yiddishkeit.”

Phillip Roth described Shabbat candle-lighting as the single island of sanctity in the life of a young boy questioning his faith: “When his mother lit candles Ozzie felt there should be no noise; even breathing, if you could manage it, should be softened.”

Shabbat candles have always had popular appeal. Not mentioned in the Torah, the practice of ushering in the Sabbath by kindling lights may have developed in antiquity. Shabbat lamps bring joy, honor, and peace to the holy day, the sages said, including the practice as one of seven rabbinic mitzvahs. The Mishnah connects this obligation to women, and subsequently, in the post-Talmudic period, a blessing over the candles was instituted. So essential did the practice become that the eleventh-century commentator Rashi asserted that the Matriarch Sarah kindled a Shabbat lamp that burned all week.

For twentieth-century American Jews, Shabbat candle-lighting was an accessible observance not requiring synagogue membership, its association with mothers giving it a special aura of nostalgia. The Barry Sisters paid homage to the glory of “My Mother’s Sabbath Lights” in the forties, and in his 1958 story “The Conversion of the Jews,” Phillip Roth described Shabbat candle-lighting as the single island of sanctity in the life of a young boy questioning his faith: “When his mother lit candles Ozzie felt there should be no noise; even breathing, if you could manage it, should be softened.”

But few of the children who fondly recalled watching their mothers perform the mitzvah continued the practice, and by 1974 it was primarily Orthodox Jews who lit Shabbat candles—almost exclusively married women.

Because Shabbat candle-lighting is easily performed using common household materials, the Rebbe’s campaign was largely a matter of getting the word out. In America, it began with a full-page ad that Sternberg placed in the Yiddish daily Der Morgen Zhurnal, urging Jewish women and their daughters to light Shabbat and holiday candles, and to give a few coins to charity beforehand. That was eventually upgraded to a long-running notice listing Shabbat candle-lighting times on the front page of the New York Times.

The campaign had a practical side as well. The Rebbe supervised the design of a brass candlestick, since reproduced an estimated 8 million times and distributed all over the world, and the popularization of tea lights in the 1980s and ’90s made it affordable for Chabad high school girls to distribute candles on street corners every Friday afternoon. But in the campaign that came to be known as Neshek—an acronym for the Hebrew words “holy Sabbath lights” that also means “weapon”—the most potent ammunition was light.

Home and Homeland

Marnie Perlstein and Elaine Chaya created their Instagram posts at the request of Rivkah Krinsky, a Chabad activist, matchmaker, and podcast host who coordinated a social media blitz for the Neshek campaign’s fiftieth anniversary. Eighty-one influencers all over the world urged their followers to light Shabbat candles as part of #HomeofLight, reaching an audience of more than three million people.

The social-media campaign’s name is a reference to the domestic nature of the mitzvah. “Light, gratitude, everything starts in the home,” Krinsky said, There is also, she noted, a second, more current reference intended: “We’re one people, with one homeland.”

The task of dispelling darkness with light seemed particularly urgent in the aftermath of October 7. In a survey conducted last year by the Jewish Federations of North America, 43 percent of American Jews expressed a new interest in engaging with Jewish life. And for many, Shabbat candle-lighting was an easy first step. American and Israeli celebrities announced that they had incorporated the mitzvah into their weekly routines. In the week after the Hamas attacks, the Lubavitch Youth Organization of Brooklyn shipped fifteen thousand candle-lighting kits all over the world.

Even people who knew little about Chabad’s campaign made the connection. Kylie Ora Lobell, a Jewish writer and publicist, posted a video on social media last winter standing in front of anti-Israel protestors at a Jewish National Fund conference in Denver—in her hand was a large bag of tea lights. “They called me a baby killer. So I handed out Shabbat candles,” she wrote gleefully.

The gloom is particularly thick online—82 percent of young Jewish adults said they had encountered antisemitism on social media—and many Jewish influencers have spent the last two years in reactive mode, combating misinformation.

“I’m entrenched in darkness and negative stories,” Perlstein acknowledged. That made her post about Neshek particularly meaningful. “I’m not a religious person. It’s interesting that I was included and that it really resonated,” she mused. “There was something about everyone focusing on doing it [candle-lighting] at the same time. The call to action was definitely heard and heeded.”

Perlstein and Elaine Chaya’s posts garnered more than a thousand likes each. Some followers commented that they had been inspired to begin lighting Shabbat candles again after many years; some committed to do the mitzvah that week for the first time.

“Layering Commitments”

Long before the advent of social media, the Neshek campaign found a large and receptive audience in the Soviet immigrants who flocked to America in the 1980s and ’90s. “We were hated and persecuted without knowing what it meant to be Jewish,” said Anna Vaysman, whose family settled in Chicago after her parents sought political asylum in 1991. Chabad’s Friends of Refugees of Eastern Europe helped the family access medical and dental care, and provided basic Jewish supplies, including tea lights for her and her mother to light on Friday evenings.

Shabbat candles are lit eighteen minutes before sundown on Friday, after which Shabbat officially begins. Timing is crucial—kindling a new flame on Shabbat is strictly prohibited, so it’s better not to light at all than to light too late. And for many people, this limitation is part of the appeal. Maintaining the practice, performing a small act each week at the same time with many others, nurtures discipline, attention, and a sense of belonging.

Often, as the Rebbe pointed out in talks about the Neshek campaign, the small flames become the point from which an awakening Jewish consciousness expands outward to transform an entire family.

Vaysman’s early years in the Soviet Union cast a shadow over her adult Jewish life. Now a mother herself, she has thought carefully about how she wants her children to experience their Jewish identity. “We’re still Soviet Jews,” she said. “My kids will practice Judaism in a different way than my husband and I do. I wanted them to do better, to really feel it and know it. They have the freedom to explore.”

Though her work schedule had made lighting Shabbat candles on time difficult, Vaysman committed to light Shabbat candles on time each week during the Covid pandemic. Five years later, she and her daughter are still lighting candles, the lighting now preceded by giving to charity and followed by a full Shabbat dinner. “Now we keep adding to that commitment,” she said. “It’s like we’re layering our commitments, and the things that we’re doing for our religion, our family, and our people.”

Step Away and Pray

In a pre-electricity world, Shabbat candles served a practical purpose. “The obligation [of lighting Shabbat candles] is due to shalom bayit, peace in the home,” the Talmud notes, and Rashi elaborates that without light, people might stumble over obstacles in their houses. But even where physical illumination is not required to prevent injury, peace and light have long been synonymous in Jewish thought: a Midrash states that G-d created light first during the six days of creation, because peace is the fundamental building block of the world. “A woman lights Shabbat candles and she raises children who illuminate their surroundings,” the Rebbe said to an audience of women and girls in 1974. “Together, they bring peace to the world.”

Twelve years as a fashion blogger and influencer left Elaine Chaya feeling in need of peace. “What I do is respond to what’s happening in the world. I have to always be on, to always come up with stuff,” she said. “It got really draining.” Observing Shabbat offered her a much-needed respite: “I really encourage people to step away and pray. I think there’s something to that.” Even one small act, she tells her followers, can make a difference in their lives.

After seeing Elaine Chaya’s post about lighting Shabbat candles, Sandy reached back into a kitchen cupboard for the tea lights a friend had given her years before. The next day, as the sun was about to set over the hills behind her house, she lit one of them and recited the blessing for the first time in twenty years.

The single flame on her kitchen counter brought back memories from the past, even as it gave her a sense of connection in the present. “I felt like I was standing in solidarity with my Jewish brethren,” she said. “Doing this all at the same time, it’s something to send out into the universe, to say, hey, we’re here, and you’re not going to destroy us.”

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of Lubavitch International, to subscribe to the magazine, click here.

Be the first to write a comment.